By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

A stone in the burial ground of Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’ Church) commemorates Sarah and Joseph M. Warner. The couple’s children had ordered the monument soon after Sarah’s death in 1867. Sadly, the body of sea captain Joseph Warner does not rest in the grave. Although time has erased almost all of the inscriptions on the stone’s marble surface, at one time they read, “Lost at sea in the year 1832,” followed by the Biblical prediction, “The earth and sea shall give up their dead.”

The circumstances of Warner’s death at sea are not entirely clear at this stage of research—although possible clues have come to light. But the story of his short life, as much as we know of it, provides a chronicle filled with adventures.

Joseph Moore Warner was born in Philadelphia in 1794. He was one of the younger children of Joseph and Charity (Moore) Warner, who had married almost 22 years earlier at St. Michael’s Zion and Lutheran Church.

The Warner family descended from Capt. William Warner (1627-1707) and Ann (Dide) Warner. Capt. Warner, born in the village of Blockley, Worcestershire, England, was allegedly an officer in Oliver Cromwell’s anti-monarchist army. After the Restoration, he fled England with his wife and children; in 1675, they settled in Gloucester, N.J. In about 1677, William Warner crossed to the west bank of the Delaware River to territory that would in a few years become part of Pennsylvania. He purchased a large block of land from the Indigenous people, the Lenni Lenape, and built his house, Blockley, on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, where the Philadelphia Zoo is now located.

His son, William Warner Jr. (1656-1712), who continued to reside in Gloucester, married Christina Svensdotter Skute. William’s wife was the daughter of the soldier Sven Skute (Swann Schuuta), who had been granted an immense tract in the area from Queen Christina of Sweden in 1653. Throughout the 18th century, Warner descendants had success as merchants, sea captains, silversmiths, cordwainers (shoemakers), cabinetmakers, Revolutionary soldiers, politicians—and more.

Our Joseph appears to have been born into one of the relatively less wealthy branches of the Warner line, though his immediate family was certainly not poor. At the time of Joseph’s birth, his father was working as a shoe stay and heel maker (a stay, or “tree,” is a wooden mold in the shape of a foot, which is used for making shoes). In the mid-1790s, the elder Joseph and his wife Charity had their home and shop in the city center, at 14 Chestnut St., west of Front St. The building had been owned previously by the silversmith Philip Syng Jr. (who died in 1789), a relative of the Warner family by marriage.

A few doors up the street, at 24 Chestnut St., Joseph’s brother, Sven Warner, also carried on the trade of a stay and heel maker. Sven rented the building from their mother, Ann Warner, who also owned other property in the district.* Sven had married Alice [—] at Christ Church in 1785, and had two sons, Mark and Joseph. The inventory of Sven’s goods at his death, in 1799, shows a number of pieces of mahogany furniture (chairs, bed, framed looking glass, etc.), six Windsor chairs, and other items that indicate the family led a relatively comfortable middle-class life. There were also “sundry shoemaker’s tools,” a lot of heels, and 29 dozen shoe lasts.

The Chestnut Street location was not far from the waterfront, and the sight of ships’ masts and seafarers might have intrigued six-year-old Joseph M. Warner. In those years, some of the more affluent Warner relatives, the brothers John and William Warner, operated a fleet of packet vessels—most notably, the Charlotte—which carried passengers and goods on the river between Philadelphia and Wilmington, Del., where the family had a store. John and William had operated as sea captains and traders with suppliers in the West Indies. In time, William established a store on S. Water Street, not far from Joseph’s house. John eventually moved into a political career, becoming a consul for the federal government in Puerto Rico, and later in Cuba.

In 1801, Joseph M. Warner’s father moved his shop and his family to 168 N. Front Street. Tragically, the elder Joseph Warner died within the year. In order to support the family, his widow, Charity, was compelled to take in boarders at their home. About three years later, they moved to the southern part of the city, at 217 S. Front Street, where Charity continued to operate a boarding house.

While still young, Joseph set about to try his fortunes in one of the family trades—as a mariner. The fact that John and William Warner had been sea captains, and that his uncle Sven’s son, Mark Warner, had also gone to sea might have influenced Joseph’s decision to do the same.

On May 16, 1807, thirteen-year-old Joseph M. Warner went with his mother to the office of a customs agent in order to obtain a seaman’s protection certificate. These identity papers served mariners as proof of U.S. citizenship, and could help ward off attempts to kidnap them to serve on foreign-flag (chiefly British) vessels. The papers described Joseph as having a light complexion and light-brown hair, with a mole on his right cheek, two moles on the right side of his neck, a cut on his left thumb, and a smallpox inoculation mark on his left arm. He was still fairly small (four feet, six inches tall).

Scarcely eight months after accompanying Joseph to get his seaman’s papers, on Jan. 6, 1808, Charity Warner died. She was 59 years old and afflicted with “decay of the bowels.” Joseph and his older siblings—Esther, Ann, William, Elizabeth, and Mary—were now orphans.

An early voyage to Portugal

A few years later, at age 18, Joseph M. Warner was working as second mate on a trans-Atlantic voyage. On March 23, 1812, he is listed in Philadelphia customhouse records as having signed onto the brig Hannah and Rebecca, under Capt. Matthew Park, and bound for Oporto, Portugal. In mid-June, the brig was reported waiting at Oporto to sail to St. Ubes (in southern Portugal) in about a week. A number of vessels had remained in the harbor until they could form convoys to help dispel predatory actions by British cruisers. Finally, on June 18, while the Hannah and Rebecca was still at Oporto, the United States declared war on Great Britain, citing as a reason Britain’s interference with U.S. shipping and its impressing of U.S. seamen.

After a stop at St. Ubes—known for its exports of wine, oranges, and sardines—the Hannah and Rebecca undertook a long voyage to the Isle of May, off the eastern coast of Scotland, where the main export was salt. The voyage must have been perilous in wartime since it required a long journey through the English Channel and into the North Sea, an area that was closely patrolled by British warships. And the Isle of May stood directly at the entrance to the Firth of Forth—where the islands and promontories contained fortifications to protect the city of Edinburgh. But there is a good chance that Capt. Park was unaware that war had been declared, and no reports have surfaced of his vessel being molested by the British.

Following a voyage of about 28 days from the Isle of May, the brig arrived back in Philadelphia during the first week of August 1812. (While Joseph had been at sea, his 21-year-old sister, Esther, married Franz (Francis) Carlotta Wittenburg on July 25, 1812.)

Two months later, on Oct. 10, 1812, Joseph Warner reapplied for a seaman’s Proof of Citizenship certificate. He testified before the notary public that he had recently lost the document that he had signed in 1807 and needed a replacement.

Wartime: A captain accused of smuggling

As the war continued, in July 1814, Joseph Warner signed onto the brig Perseverance, commanded by Capt. John Whitney and bound for Barbados and other islands of the West Indies. The Perseverance was operating as a cartel—a vessel that was authorized to sail under a flag of truce in order to transport war captives during a prisoner exchange.

On the return voyage, the Perseverance left Barbados on Oct. 21, having been ordered by John Barker, the British agent for prisoners of war who was stationed on the island, to proceed directly for Philadelphia, without stopping at her previously arranged destination of Jamaica. The Perseverance arrived back in Philadelphia on Nov. 6.

Some days later, another vessel brought back to Philadelphia a newspaper from Barbados, The Times, which carried a scathing attack on the conduct of Capt. Whitney. The paper maintained that he had ordered the brig to set sail for Philadelphia while leaving all of the released prisoners behind on the island (i.e., under the jurisdiction of the enemy), in order to cover up his participation in a smuggling operation.

The Barbados newspaper’s charges against Whitney were quickly repeated by the Philadelphia Aurora (Dec. 3, 1814). The article alleged that after the Perseverance had left the harbor without its passengers, several boats were sent out to overtake it. However, it said, “the master of the brig, it seems, refused to heave to, to permit them alongside. The reason for this disgraceful and inhuman behaviour is stated to have arisen from fear of a seizure in consequence of his having been concerned in smuggling and other shameful violations of the honorable neutrality of a flag of a truce.”

For the next month, the article with its scandalous charges against Whitney was reprinted in newspapers up and down the Eastern seaboard. Obviously, if the allegations were true, he was liable to be indicted for treason! And even a young seaman like Joseph Warner might come under suspicion on the accusation of smuggling.

Soon after the article appeared in the Aurora, and the malicious rumors began flying around the country, Whitney wrote a letter to the Aurora’s editor in order to vindicate himself and to do “justice to my country and the flag [of neutrality] that I then bore.” He reported that in the early afternoon of Oct. 24 he had picked up a few passengers on the leeward side of the island and made ready to sail, in accordance with the orders of the British agent for prisoners of war. Furthermore, “I lay by until they had got their baggage out, and no other persons appearing, at 2 p.m. I made sail; at 10 p.m., I was brought to by the [Royal Navy] schooner Flying Fish … the commander of which told me that captain Brewer [the person who had chartered the brig] had informed the senior officer at Barbadoes [sic] that I had British produce aboard. … After examining me, he permitted me to proceed, observing at the same time that he saw through the motives of the villain who had given such false information.”

“As to leaving passengers behind,” he continued, “It is equally as false; there was but one passenger offered for America, and him I brought home, Charles Walton by name, an American Citizen discharged from the British.” There were also two released American prisoners, he said, who had been ordered aboard the Perseverance but failed to appear for the voyage. As evidence that he was innocent of the scurrilous charges, Whitney enclosed a copy of the orders given to him by the British agent Barker; this too was published in the Aurora and reprinted in the New York Herald (Dec. 12, 1814).

Marriage and birth of their first child

The issue was resolved, and the charges that had been lodged against Capt. Whitney soon disappeared from the press. He and the Perseverance made a second voyage to the West Indies as a cartel in the spring of 1815. In the meantime, however, Joseph M. Warner signed onto another vessel—the brig John Burgwin, under Capt. Samuel C. Montgomery—sailing to Gibraltar by way of Wilmington, N.C. The brig was named after the prosperous colonial official and merchant John Burgwin (1731-1803), who resided in the latter city, and owned several slave plantations in the Cape Fear River area. After Burgwin’s death, his sons carried on the mercantile operation in Wilmington.

The vessel departed from Wilmington on March 29, 1815, and arrived in Gibraltar 31 days later. (An official letter signed by President James Madison and Secretary of State James Monroe, asking for unmolested passage for the Burgwin on that voyage, was offered at auction in 2009.) In late June, the John Burgwin left Gibraltar; she arrived back in Philadelphia on Aug. 16 with a cargo of wine, raisins, and currants to be sold by the auction house of Frederick Montmollin and Solomon Moses—a partnership of two Jewish merchants.*

While in Philadelphia between ships, Joseph Warner married Sarah Taylor. The ceremony took place at St. Paul’s Church on Sept. 5, 1815. But the newlyweds had little time to spend together. Two weeks ater the wedding, on Sept. 22, Warner again sailed on the John Burgwin—this time to Madeira under Capt. James Robbins. He probably served as a mate.

On Oct. 22, 1816, Elizabeth, the Warners’ first child, was born. She was baptized at Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’ Church) on March 23, 1817—though her father was at sea at the time of the event.

Two months earlier, in January 1817, Warner had gone to New York City to sail once again (probably as a mate) with Capt. Montgomery. At age 23, he was listed as having grown to five feet, six inches in height. They took the brig Manufactor on a four-month voyage from New York to Antwerp. A couple of weeks before she left port, the Philadelphia merchant Joseph S. Lewis had purchased the vessel at the Tontine coffeehouse, at the corner of Wall and Water Streets in New York, which was the general meeting and trading location for the New York merchants and brokers. The vessel was being sold by the Wall Street auction house [Martin] Hoffman & Glass, located nearby at 67 Wall Street. The Manufactor was fairly new, having been built in 1811, and Lewis later advertised her as being “extraordinarily fast sailing.”

Upon arrival in Antwerp, there might have been a mishap, since three crew members had to be left at the hospital and given three-month’s pay. The brig returned to the merchant firm of Joseph S. Lewis in Philadelphia on May 6 with a cargo that included 20 cases of muskets, three tons of zinc, 100 tons of coal, and books, paintings, garden seeds, and other assorted merchandise.

Appointed as a sea captain; assaulted by thieves

The following January (1818), Joseph Warner passed a significant milestone in his life when he was appointed master of the Manufactor. On that voyage, the U.S. government paid Capt. Warner $10 to transport an ill and destitute seaman from Hamburg to Philadelphia.

For a few years, Warner voyaged mainly to Cuba and the West Indies, including five voyages on the brig Caledonia in 1820-21. On Aug. 9, 1821, while in Philadelphia, he signed his will, leaving his estate to his wife Sarah. Also mentioned were his sisters Esther Wittenburg and Ann Emerland. As executors of the will, Warner appointed his cousin Joseph Warner (Sven’s son), now a silversmith, and Thomas Sparks, a plumber. Sparks was the owner of the shot tower (used to make musket shot from poured molten lead), which was a landmark on the skyline, rising 350 feet in the district of Southwark.

It is curious that at the young age of 27, Warner felt the need to write a will. It is doubtful that he was gravely ill at the time, since he embarked on another sea voyage just two days after signing the will. It is possible that the perilous conditions he had witnessed at sea convinced him that it would be best to provide for his family at this time in case of his demise. This might have been reinforced by the fact that voyages to the Caribbean in particular were encountering more and more attacks by pirates and cutthroats in the 1820s. At the same time, the illegal slave trade was increasing, due in part to the need for labor in the expansion of sugar plantations in Cuba. And Cuba itself was becoming a transit point for the shipment of enslaved Africans to the cotton plantations of the U.S. South.

It was even possible that Capt. Warner had a foreboding of the dangerous situation that he would face on his coming voyage. On the very day that he signed his will, Thursday, Aug. 9, Warner and the Caledonia left Philadelphia for Cuba. Late in the night of Sept. 6, while the brig was lying in Havana harbor, she was boarded by 14 robbers, armed with pistols, cutlasses, and daggers. The New York Evening Post reported (Sept. 25, 1821), “The captain of the Caledonia was the first person that was knocked down, after which all hands were put in the forecastle, and capt. Warner and the mate plundered of everything, and the vessel robbed of 85 boxes of candles and her small boat.”

The report continued, “They, however, on the next morning, recovered 33 of the boxes, and expected to get the remainder, by the circumstance of one of the gang turning evidence against the others.” A later account in the Evening Post (Nov. 12, 1821) stated that goods worth about $2500 had been stolen, though it was not clear whether that sum referred to before or after some of the material had been recovered.

The Sept. 25 article pointed out that about seven or eight other vessels in Havana harbor or of the coast of Cuba had been robbed the same week as the Caledonia. In fact, on the very night that the Caledonia was attacked, the Ajax of Philadelphia, under Capt. Shain, had about $1000 worth of property stolen while moored in the harbor.

On Feb. 22 of the following year, the Warners’ daughter Sarah was born. It was, of course, the day to commemorate Washington’s Birthday. The First Company of the Washington Guards assembled in the City Square at 9 in the morning for a parade. The First Troop, which met outside Sixte’s tavern, across from Washington Hall, began their parade at 10 a.m., to be followed by a lavish dinner at Witmer’s Hotel at 4 p.m. Also in the morning, the National Guards, the Third Company of the Washington Guards, the First Regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the Volunteer Military Association, and the Washington Blues all assembled at various locations for parades across the city.

So, little Sarah chose a tremendous date for a birthday celebration! She was baptized on Oct. 26, 1822. And about that time, the Warner family moved to a house at 15 Mary Street (later called League Street), a block to the south of Gloria Dei Church and Sparks’s shot tower.

On board the Margaret: Pirates and revolution

In March 1823, Joseph M. Warner signed up as master of the brig Margaret, which was owned by Patrick Hayes and his sons. The elder Hayes, a nephew of U.S. Navy hero John Barry, had been a sea captain for many years. After 1810, however, he retired into a new career as a commissions agent in commercial trading, while his sons did most of the actual sailing. He was married to Elizabeth Keen, a descendent of the 17th-century Swedish settler Jöran Kyn.

The Margaret left Philadelphia on March 10, 1823, bound for Alvarado, Mexico. The town, on the Caribbean coast, about 45 miles by sea from Veracruz, had a protected harbor and served as one of the chief ports for the country, with roads to the interior cities of Puebla and Mexico City. Political conditions were extremely unsettled in the region at the time. In December 1822, Antonio López de Santa Anna, formerly the head of the port of Vera Cruz and a local caudillo, rebelled against the government of the self-proclaimed Emperor Augustín I (Augustín de Iturbide). In May 1823, about the time that the Margaret was in port at Alvarado, Iturbide abdicated, but factional conflict and rebellion continued.

In the meantime, acts of piracy mounted. For example, Capt. Toscan of the Gossypium wrote to the vessel’s British owners from Havana on April 8, “Yesterday, ten miles from the Havana, was boarded by a piratical schooner, with from 30 to 40 men. We were ordered on board the schr. where I was beaten, hanged and thrown overboard; all the crew were more or less beaten, and a man named Elwell was wounded in two places and hanged until apparently dead; another badly wounded with a dagger. … They robbed us of all our clothes, small stores, boat, and about eighty dollars in money, and then allowed us to proceed.”

Capt. Goddard, from the Boston brig Margaret & Sarah, wrote on the same date, “Night before last, the pirates attempted to rob an American brig, close to the Moro [castle at Havana]; and last night they robbed the Three Sisters (while lying off and on) which sailed from Boston in co. with me, and killed her mate (Mr. William Wilkinson, a native of Marblehead, aged 32). The coast swarms with pirates, and it was a miracle that I escaped them.” And when the brig Nancy arrived at Marblehead, 34 days from Pernambuco, the captain reported, “boarded the wreck of schr. Illinois, of Boston, mainmast gone, full of water—saw two dead bodies in the cabin, supposed to be the captain and the mate—she had been previously boarded and stripped of everything except jib boom, windlass, and fore shrouds” (The Farmers’ Cabinet, Amherst, N.H., May 3, 1823).

After a 20-day voyage from Alvarado, Warner and the brig Margaret arrived back at Philadelphia on July 1 with a cargo of cochineal and lumber. Warner stated that he had seen a number of pirates cruising off Campeche (i.e., along the Yucatan peninsula); the pirates chased the brig—both on the way to Alvarado and on the return trip—but they managed to escape (The New York Evening Post, July 2, 1823).

Barely more than a week later, on July 9, the Margaret was back in service on a voyage to Hamburg, Germany, where she arrived on Aug. 12. Unfortunately, the brig grounded on a bar of the Elbe River; it appears that several members of the crew were injured and had to remain in the hospital. After repairs, the Margaret left Cuxhaven, the port at the mouth of the river, on Oct. 11. Originally, the newspapers reported that she was bound for New Orleans, but at some point her course was set again for Alvarado, Mexico. The voyage proved to be extremely eventful.

In November 1823, after crossing the Atlantic and en route for Alvarado, it appears that Warner and the Margaret stopped at Havana, Cuba. Newspapers at the time reported that four crew members of the brig Margaret from Philadelphia were among a group of American and British seamen who were charged by the authorities of being accomplices to the murder of a Spanish mariner, Felipe S—, on Nov. 10, 1823, on the quay at Havana. The men—Charles Perry, 36, Joseph Poole, 28, John J. Fenimore, 23, and John White—were arrested and lingered in prison without having had a trial for well over a year. At the same time, two other members of the crew deserted from the Margaret in Havana. Warner hired eight men to augment the crew before leaving port.

About Nov. 28, while approaching the Campeche bank in a gale, the brig Margaret passed within half a mile of a large American ship, with brightly painted sides. The foremast of the ship was cut away, and all her sails were gone except her jib, which was hanging loose on the bowsprit. Because of the high winds, the crew of the Margaret was unable to board the apparently abandoned ship and sailed on.

On Nov. 30, Joseph Warner and the Margaret spied a black schooner—obviously a pirate vessel—lying to under the mainsail and the jib. The topsail and the jib boom were missing, indicating the possibility that the vessel had suffered damage either in a storm or in a battle. As soon as the schooner spotted the Margaret, she made sail and kept the brig under watch for four days. Warner could see through his glass that the pirate schooner had an unusually large crew on board, about 50 men, mostly Blacks. He supposed that they had attacked the ship that they had seen at Campeche and had robbed and murdered all who were aboard (see Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, Jan. 3, 1824). But the question remained unanswered as to why there were so many Black men on board the schooner. Perhaps the hulk at Campeche had been an illegal vessel in the slave trade, carrying kidnapped Africans to labor on the Cuban sugarcane plantations—and the pirate schooner had liberated the slaves.

The pirates chased the Margaret all the way to the sand bar outside the harbor at Alvarado. Unfortunately, although the brig was able to elude the pirates, on Dec. 3, she got stuck on the bar. With difficulty, the crew was able to free her, but soon ran aground in the harbor. That night, with both pumps going, they were able to extract the cargo and found only about 80 packages damaged. However, the brig continued to fill with water and capsized (see ibid. and Lloyd’s Marine List, June 30, 1824).

As luck had it, another vessel owned by Patrick Hayes and his sons, the ship Tontine, arrived in Alvarado harbor just a day or two behind the Margaret. The Tontine’s master, 23-year-old Thomas Hayes, took charge of raising the Margaret, and soon had her afloat again.

As it turned out, the Tontine had had its own sighting of the pirate vessel, on Dec. 4 and 5. Having unloaded its cargo at Point Lizardo, about 30 miles to the north, the Tontine approached the bar at Alvarado while the British brig Marquis was off the bar at the same time. Suddenly, the pirate schooner bore down on the Marquis and hailed her, inquiring whether the Spanish or Mexican fleets were in the vicinity, and what other vessels were in the harbor. The British captain informed them that the Spanish fleet was under way from Point Lizardo toward Alvarado.

The situation certainly was dire. Spain had sent warships and men to intervene in the revolt in Mexico on the side of the government, with the objective of trying to grab some territory; they still held the castle above Santa Cruz and were bombarding the town. It is quite possible that the crews of the vessels at Alvarado could hear the cannon fire in the distance.

On hearing the news of the proximity of the Spanish fleet, the pirates quickly raised the colors of Spain as a decoy and made full sail. It is curious that the pirates were able to get away unmolested. While this was going on, according to a report by another sea captain, S.J. Lewis of the brig Orleans, the Mexican Navy had its own fleet, consisting of four schooners and five gunboats, lying idle inside Alvarado harbor. Lewis noted with disgust, “They had not been out for several weeks, though a pirate was off the harbor” (New Orleans Courier, Jan. 26, 1824). It is possible, of course, that the Mexican naval vessels feared the approaching Spanish fleet as much as the pirates did, and wished to avoid an encounter.

Hayes takes over the Margaret; Warner takes the Tontine

Capt. Hayes and Capt. Warner then switched command of the two vessels. Warner took charge of the Tontine, and was soon underway to Havana, Cuba. The ship unloaded a cargo of Indian corn, vermicelli, smoked herrings, hides, and casks of vinegar, according to the receipts from the merchants Murdoch, Storey & Co. in Cuba. She then loaded on a cargo of coffee, oranges, cigars, pineapples, yams, plantains, sweetmeats, and other vegetables bound for Philadelphia, where she arrived at the beginning of April. Later accounts show that Warner was paid $150 for his services as master of the Tontine from Jan. 8 until Feb. 23, 1824. He was paid an additional $90 for the voyage from Feb. 23 until being relieved in Philadelphia on April 23, 1824. (All of the cited documents are on file at the Independence Seaport Museum).

While Warner was sailing the Tontine to Cuba, Thomas Hayes supervised the remaining repairs to the brig Margaret and hired a new crew. When it was judged ready for service, the Margaret was given a special mission to carry a number of rebel officers from Mexico into exile. Originally, the rebels had been sentenced to death, but on the day appointed for their execution, Iturbide asked the Congress to commute the sentence and change the punishment to banishment. The prisoners were conducted under guard to Alvarado, where they boarded the brig Margaret (Philadelphia National Gazette and Literary Register, March 18, 1824).

Later, on March 8, a friend and business associate of Patrick Hayes, J. Reilly, wrote to Hayes from Havana about the negotiations that had transpired in Mexico. Reilly stated that “the Margaret was chartered for 3000 dollars to go from hence [Alvarado, Mexico] to Laguira [La Guayra, Cuba] with 8 or 10 passengers [later expanded to as many as 22 passengers]. Persons banished by Government from this Country. When Thomas [Hayes] consulted me, I gave Him my Opinion that he had best return Home in the Brig” (letter in the collection of Independence Seaport Museum, Barry Hayes Papers).

Simultaneously, the Mexican government ordered two French officers out of the country. The accused men were “Monsieur de Smaiths,” identified elsewhere as Julien-Désiré Schmaltz—French colonel of engineers, survivor of the famous wreck of the Medusa in 1816, and French governor of Senegal until August 1820—and Achilles de la Motte, Schmaltz’s secretary and also a colonel of engineers. Both men had entered Mexico in February 1823 under the guise of being French merchants and were arrested and imprisoned under charges of acting to further the designs of the Bourbon royalty to once again rule Mexico. They had been captured after the Mexican authorities discovered their correspondence, some of which was written in code, which appeared to implicate them in espionage. However, rather than sentence them to death as spies, the regime banished them to New Orleans (Philadelphia National Gazette and Literary Register, April 15, 1824). It is likely that the Margaret carried these two men as passengers, as well as the 22 rebel officers.

The brig sailed from Alvarado in convoy with several other vessels as protection against pirates, but she did not go to Cuba, as was originally planned. Instead, she stopped in Belize, and then reversed course, arriving in New Orleans on Feb. 7.

At New Orleans, Thomas Hayes entrusted the Margaret to the command of a Capt. Oliver, while he made his way overland to Philadelphia. He wrote to his father on March 13, in a letter now at the Independence Seaport Museum: “I have just clear’d the Margaret out for Philad. in Balast & Oliver goes in her. Intend making tour through our western Country for the sake of information and shall stop at Washington in my Route …” While in Washington, Thomas Hayes wrote, he hoped to meet with the Secretary of the Navy, and he asked his father to try to obtain a letter of introduction to the cabinet member. The brig Margaret, he added, was a “staunch” and “remarkably fine vessel.” The Margaret left New Orleans the following day and arrived in Philadelphia on April 1 (National Gazette, April 2, 1824).

In Philadelphia, the brig Margaret underwent additional repairs and refitting (receipts for the work are in the collections of the Independence Seaport Museum), and was entrusted once again to the command of Joseph M. Warner. On April 29, the brig was sent on a quick voyage to La Guayra, Cuba, with 50 kegs of butter, 10 barrels of pork, four barrels of ham, and 882 barrels of corn in her hold. The Philadelphia merchant firm of Robinson & Foley commissioned the vessel from Patrick Hayes. The Margaret returned from La Guayra on July 21 after two weeks at sea. She carried the goods that had been obtained in trade in Cuba—including over 300 bags of coffee, 309 bags of cocoa, 205 hides, and 200 boxes of white and brown Havana sugar; all of it was disbursed to various Philadelphia merchants.

In September 1824, Capt. Warner was assigned to make another voyage on the brig Margaret—this time to Europe. In November of that year, little Sarah Warner Jr. died; she was just two years old. But her father was still at sea and did not return home for many months.

On Feb. 3, 2025, Warner and the Margaret met another vessel, the Moss, which was returning to Philadelphia after leaving Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) 115 days earlier. The encounter took place in the open ocean (lat. 26 N, long. 70.14 W), several hundred miles east of the Bahama Islands. Capt. Warner reported to the Moss’s captain that they had experienced extremely rough weather on the voyage from Santander, Spain, and now after 43 days at sea, the Margaret was not far from her destination—Havana.

For most of March, Warner and the brig Margaret remained in Havana. There is a possibility that Warner was able to visit his former crew members who were in prison and charged with complicity to a murder during their November 1823 stopover in that city. Certainly, he would have argued on their behalf—especially in conversations with his cousin, U.S. Consul John Warner. In early 1825, U.S. officials who had looked into the case stated their opinion that there was little evidence to implicate the men (The New York Evening Post, March 29, 1825). And John Warner expressed “hope that he may obtain their release” (Portland Advertiser, April 2, 1825). However, the consul was extremely ill and had to delegate most of the inquiry to other officials from his office. Although the consul had been advised by doctors that his health would continue to deteriorate in Cuba’s tropical climate, he had struggled to obtain a transfer to a station where the weather was cooler. Finally, in April 1825, John Warner was able to return to the United States—but died the following month.

On March 27, 1825, the brig Margaret left Havana, sailing again for Santander. And in turn, she departed Santander on May 17 to return to Havana, arriving after a 50-day voyage on July 5. After loading her cargo at the Havana quays, it was finally time to return home! Following a two-week voyage from Cuba, the Margaret sailed up the Delaware to her berth at the Philadelphia docks on Aug. 13, 1825, with a cargo of sugar and limes. Capt. Warner had been away from home for eleven months. That year, the family moved from Mary St. to 518 S. Front St., opposite the U.S. Navy shipyard at Front and Federal Streets. (In the mid-1830s, soon after Joseph Warner’s death, the address was changed to 1006 S. Front St.)

Two weeks after coming into port, on Aug. 31, Warner and the Margaret sailed once again for Santander—their final voyage together. Warner served over two years as master of the Margaret, and although there had been many mishaps during that time, the brig always emerged for another voyage. His next vessel, the ship Prudence was not as lucky.

The Prudence: A leaky ship

The ship Prudence was advertised by her owner, J. Welsh, as being “a swift vessel, with a large cabin and six furnished staterooms. She had been purchased only a few weeks before sailing. Perspective passengers were advised that although the ship would be sailing for Hamburg and Londonderry, they might also land at Calais, Dover, or other more convenient ports on the English Channel. In short, the Prudence was a luxury ship, whose owners strived to accommodate their wealthy customers.

The Prudence sailed from Philadelphia on Feb. 26, 1829, but did not go very far across the Atlantic. She encountered heavy weather, began to leak badly, and most likely was blown off course. The ship managed to limp into St. George’s, the capital of the Bermuda Islands, arriving on March 18. After two weeks, on March 30, the ship was determined to be unseaworthy and was condemned.

The mates and crew of the Prudence were carried back to Philadelphia on board the brig Orbit, under Capt. Binney, which had stopped at St. George’s on her return from Europe, with a cargo of horsehair, flax, furs, sailcloth, cordage, etc. The Orbit left St. George’s on April 3. Capt. Warner, on the other hand, appears to have remained in Bermuda for a while, no doubt in order to handle business matters that included disposing of the wreck of the Prudence and her cargo, redirecting the bags of mail that she had carried, and preparing reams of paperwork. Presumably, the passengers on board the Prudence, who were now marooned in Bermuda, were left to try to enjoy the island’s beaches while seeking alternative passage to Europe.

In October 1829, Capt. Warner, now back in Philadelphia, was placed in command of the brig Eliza. The brig left the city on Oct. 10 for Vera Cruz and returned on Dec. 28. They made a second voyage to Vera Cruz on Jan. 9 and returned April 17. The only mishap on the voyage was that the mate, Frederick Venohn, 27, fell overboard and was feared lost; however, he appears to have survived and was able to ship out again in April. On April 24, Warner took the Eliza on another voyage to Vera Cruz, returning to Philadelphia on July 24, 1830.

Packet service to New Orleans

The following year, Warner was placed in command of the brig Treaty for regular packet service to New Orleans. The vessel had recently returned from a voyage to Brazil, and almost immediately was put up for sale. In preparation for the March 24 auction at the Merchants Coffee House, on Second St., the brig was advertised as having been constructed of the “best materials,” with a coppered hull and nearly new sails. She had been built in Philadelphia five years earlier (The Daily Chronicle, March 18, 1831).

The Treaty was purchased by the Water St. merchant Samuel Comly and immediately moved to a berth at Girard’s upper wharf, where loading began for her departure to New Orleans. Again, she was advertised as “a superior vessel,” with “handsome accommodations for passengers” and the capacity to carry 2250 barrels of cargo (The Daily Chronicle, April 11, 1831). She set sail on April 20 and arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi on May 28, where the steamer Post Boy hauled her over the bar and upriver to New Orleans. It appears to have been a short and uneventful voyage: Warner and the brig Treaty arrived in Philadelphia on July 21 with a cargo of cotton.

Capt. Warner immediately began preparations for another voyage, sailing for New Orleans on Aug. 15. Part of the Treaty’s cargo consisted of 30 cases of men’s hats. By Aug. 22, she was sighted off Chincoteague (on Virginia’s Eastern Shore), and on Sept. 5, she was in the Gulf of Mexico, west of Florida (lat. 27 N, long. 85). She arrived in New Orleans 10 days later. After a quick return to Philadelphia, the packet once again sailed for New Orleans, arriving on Sept. 29 with more men’s hats. On Oct. 15, the brig Treaty was off again to Philadelphia, arriving on Nov. 11 with a cargo of Kentucky tobacco, molasses, pork, 78 empty porter casks, 128 bales of rope cuttings (for paper makers), 18 bales Spanish moss, 12 bales of cotton, and other assorted merchandise.

That appears to be Joseph M. Warner’s last voyage as a sea captain. For most of the past year, he had made three rather routine voyages back and forth to New Orleans. Now, it appears that he was ready to try another trade. He listed himself in the street directory of that year as a “shipwright” rather than as a sea captain.

The schooner Dolphin: Lost at sea

In 1832, Warner partnered with John C. Rohneke to purchase the schooner Dolphin. The Dolphin was not a new vessel; she had been built in Caroline County, Md., in 1816 and had been enrolled at Oxford, Md., in 1830. The two partners registered their acquisition in Philadelphia on May 22, 1832, as she was made ready to sail. Capt. George Seaman was hired to command the schooner, with a crew of three men.

The Dolphin sailed the next day, bound for the Bahamas. Unfortunately, on May 27, almost as soon as she reached the open sea, the schooner sprang a leak. The schooner President Jackson, from Troy, Mass., encountered the vessel as she was foundering off the coast of the Delmarva Peninsula (lat. 37.48 N, long. 74.40 W). The President Jackson was able to strip the sails, rigging, and anchor from the Dolphin, as well as retrieving part of the cargo. She also took the captain and crew on board and brought them into Norfolk, Va.—while the hulk was left to sink into the ocean.

None of the crew members ever sailed again. They included John L. H. Webb, of New Castle, Del.; James Downey, on his second voyage; and James N. Goodwin, a 10-year-old boy. However, Capt. Seaman did return to Philadelphia and was appointed master of the schooner Robert Adams the following month.

Was Joseph M. Warner on the Dolphin when she sank? It is curious that he was reported “lost at sea” at the same time that his schooner was also lost.

It would not be surprising to learn that he had decided to ride on board his newly purchased vessel, perhaps as a test. And perhaps he was also serving as the vessel’s supercargo, in order to conduct trade negotiations once they arrived in the Bahamas. However, no information has come to light to confirm either of those scenarios.

It took almost a decade for Sarah Warner to be able to settle her husband’s will. She had succeeded Thomas Sparks and Joseph Warner (the silversmith) as executors of the will. On Dec. 18, 1839, Sarah appeared in a hearing on the terms of her claim, at which time it was determined that up until June 21, 1831, with the sale of furniture ($300) and other items, and with cash in hand, her husband’s estate was worth $6034. But still the estate was not settled until Sept. 14, 1841.

Sarah Warner died on Jan. 20, 1867, at age 69, due to burns. At the time, she was living at 1006 S. Front St. It was probably the same house that she had shared with Joseph M. Warner and their family when he was lost at sea almost 35 years earlier.

NOTES

* Solomon Moses, originally from New York, settled in Philadelphia after marrying Rachel Gratz (sister of Rebecca Gratz) in 1806. He partnered with Frederick Montmollin in the auction house from 1811 until 1818.

** In her will, Ann Warner left legacies to her grandchildren, Joseph and Mark Warner, sons of her late son Sven (died 1799), and to the children of her late son Joseph (died 1801). The remainder of her estate, including a building and lot on Carter’s Alley, were left to her daughter, Ann Wiltberger. Ann and her husband, Christian Wiltberger, were appointed executors of the will.

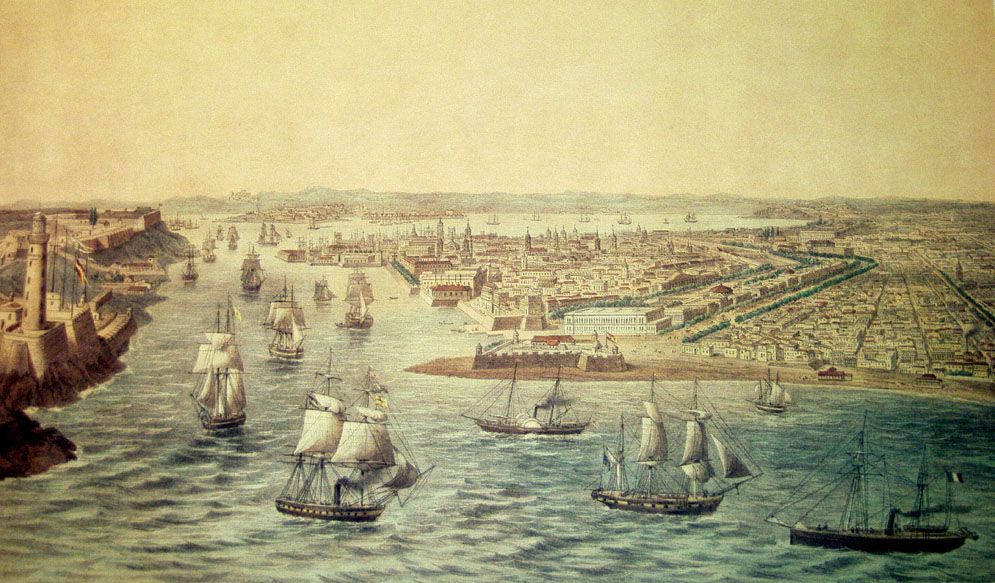

Illustration: Havana harbor in the early 19th century. Capt. Warner landed in Havana on many voyages.