By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

APRIL 15, 1826—The day began with great promise. Who would have suspected that after nightfall, two respected businesses would be robbed on Market Street?

The winter had been cold and icy, and an epidemic of influenza had made many people miserable. But now the fruit trees were in bloom. On this bright spring morning, people thronged into the streets, eager to feel the sun on their faces.

High Street (more and more frequently called “Market Street”) was packed with Saturday shoppers. At the Front Street end of the market shambles, where the fishmongers congregated, the city had recently erected a new pavilion. The columned structure resembled a classical temple and was widely admired as a practical ornament for this “Athens of America.” About 15 years earlier, New York had overtaken Philadelphia in population and commercial prowess. And tonnage at the Delaware River port even fell behind that of Baltimore. But Philadelphia was still growing and making progress; city leaders had high hopes that appropriations for new canals, highways, and steam power could restore its national preeminence.

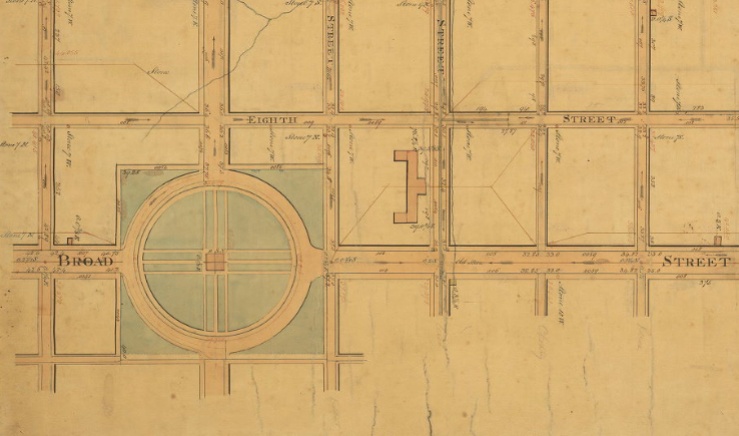

The market shambles had been recently extended all the way out to Eighth Street, in order to better serve Philadelphia’s newer neighborhoods. Here too, a large and diverse population, from the wealthy to the poor, patronized the hucksters’ booths under the shambles. And the more permanent shops also did a thriving business.

On this western stretch of Market Street, the crowds of shoppers were served by modern improvements—sidewalks were built of brick and lit with whale oil at the intersections. Many residents could remember when this area was open countryside; but within a generation, the woods and farmland had been leveled, and streets and alleys were cut through and filled with rows of redbrick houses and shops. Now western Market Street and its adjacent streets were quickly becoming the commercial center of Philadelphia.

Hansell’s clock and watch shop

Some shoppers might have had the occasion to visit the premises of James Hansell, a clock and watchmaker, at 226 Market (two doors east of 7th Street). There they could find a great variety of well-crafted timepieces, some of them encased in gold.

James Hansell, 35, had become a well-known craftsman on western Market Street, having operated a store a block away for a decade. He was the son of a blacksmith in the village of Darby. After his father’s death in 1800, nine-year-old James moved with his mother, Sarah, and his six brothers and sisters into the city. In 1814, at age 23, James Hansell served briefly in the State Guards during the war with Britain.

In 1816, he bought a house at 180 Sassafras (Race) St., between 4th and 5th. The same year, he opened his first retail shop for clocks and watches at 3 N. 6th Street, one door north of Market. His brother William operated a dry goods store further up the block, while his Aunt Sarah had a shop across the street. The following year (1817), James married Ann Catherine Ehrenzeller, who was five years younger. The couple remained in the Race Street house, and raised their children there, until the end of the 1820s.

After nine years on 6th Street, in 1825, James Hansell moved his store a block away to the 7th & Market location. (This building had been built by livestock dealer, Pennsylvania Assembly member, and famous diarist Jacob Hiltzheimer in 1794, next to his own home at the corner. It was used for a variety of businesses until Hansell moved in.)*

A digression from the story: History at 7th & Market

Less well-heeled customers in the area might have passed by Hansell’s shop, but have been attracted to The Cheap Shoe Store, at 232 Market Street, two doors west of 7th. They could purchase Gentlemen’s Boots at $4 a pair or Ladies’ Valencia Shoes, fully trimmed, for merely $1.

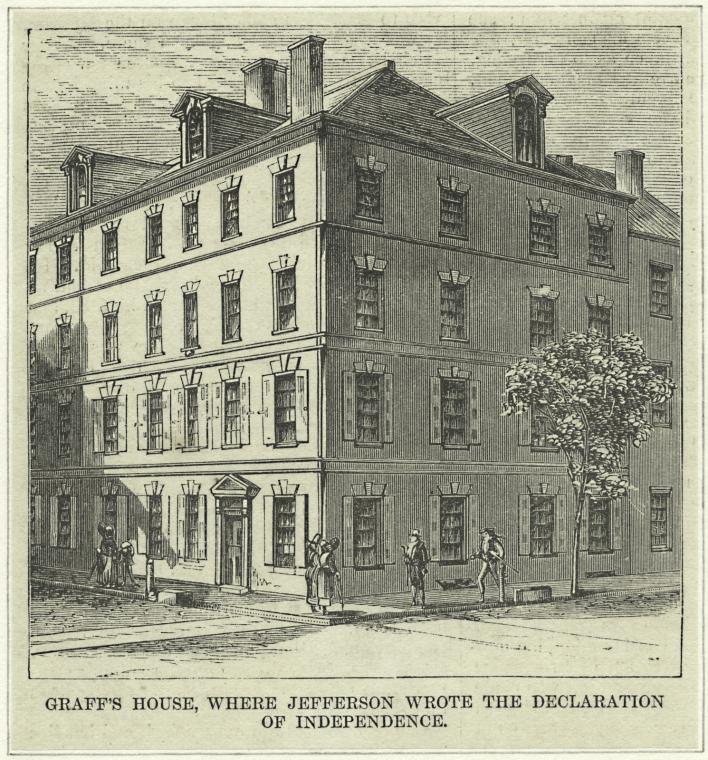

The Cheap Shoe Store stood next to an almost identical building on the corner, which had been built at least two decades earlier than its twin—when farms were still common in this area of the city. In 1775, Jacob and Maria Graff, a young couple who had married a year earlier, had the corner house built as their residence. A year later, in the early summer of 1776, they took in Thomas Jefferson as their boarder. Jefferson was attracted by the somewhat remote setting of the house. Soon after arriving in Philadelphia, he wrote to a friend, “I think, as the excessive heats of the city are coming on fast, to endeavor to get lodgings in the skirts of the town where I may have the benefit of a freely circulating air.” A week later, he had found the Graff’s house, and moved in, paying 35 shillings a week.**

Jefferson shared his rooms with his valet, Robert Hemmings, who was the enslaved half-brother of Jefferson’s wife, Martha (Jefferson called Hemmings a “bright mulatto”). And it was there in his second-floor apartment that Jefferson, as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress, penned the draft for the Declaration of Independence.

A couple of years later (July 1777), the house was sold to Jacob Hiltzheimer (who later constructed the building containing Hansell’s clock shop). In 1796, Hiltzheimer had the twin building (which later housed The Cheap Shoe Store) constructed. In that period, James Wilson, an author of the U.S. Constitution, lived in the corner building while he was serving as a Supreme Court justice. Hiltzheimer died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1798, and in 1801, both buildings, 230 and 232 Market, were acquired from his heirs by the Jewish merchants Simon and Hyman Gratz. A few years later, the Gratz brothers added a fourth story onto the pair and converted the newer building into stores. They maintained the “Declaration House” as a store and as their offices until the year of our story, 1826, when their business failed.

In April 1826, the Gratz brothers were still in business at the corner house (selling sugar, gunpowder, Nankeen cloth, floor matting, etc.). Probably very few of their customers realized that the house had important historical associations. But looking ahead three months, its role in history became better known. On July 4, 1826, Thomas Jefferson died. His notes about the house, contained in a letter he wrote a few months before his death to the scientist Dr. James Mease (author of “The Picture of Philadelphia”) began to be circulated, since 1826 was the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

The following year, in April 1827, Nicholas Biddle, president of the Bank of the United States, spoke of the house in his “Eulogium on Thomas Jefferson,” delivered before the American Philosophical Society and published subsequently in a pamphlet. Biddle observed: “These lodgings, it will be heard with pleasure by all who feel the interest which genius inspires for the minutest details of its history, he had selected, with his characteristic love of retirement, in a house recently built on the outskirts of the city, and almost the last dwelling-house to the westward, where in a small family he was the sole boarder. That house is now a warehouse in the centre of Philadelphia, standing at the southwest corner of Market and Seventh streets. There the Declaration of Independence was written.”

Nighttime at the Red Lion

Let’s pick up the story again after nightfall on April 15, 1826: The crowds had left the intersection of 7th & Market Streets. The clockmaker Hansell and his neighboring storekeepers had shuttered their windows and locked their doors, and the farmers had loaded up their remaining wares from the market. The watchmen were making their first rounds; one by one they lit the street lamps. They might have checked some of the door bolts to be sure they were fastened, while keeping an eye out for suspicious activity.

But there was still life on the street. Some people were bound for amusements in the vicinity. A light comedy was drawing crowds to the Chestnut Street Theatre, and the Philadelphia Museum, in the upper rooms of the State House, was presenting a magic lantern show; tickets were 25 cents, with half-price tickets for children.

In the meantime, many adjourned to the taverns; there were quite a few on High Street, such as the old Indian Queen, near 3rd, and the Spread Eagle, near 8th Street. Just a few doors down the street from Hansell’s shop was the popular Sign of the Red Lion—one of Philadelphia’s premier hostelries, run by Titus Yerkes.

In fact, some of the revelers at the Red Lion might have noticed a certain young man on the premises who plays a role in our story. Newspapers later described him as being “of small stature, good looking, and genteelly dressed” (New York American, April 27, 1826). Indications are that the man seemed pleasant, though it is doubtful that he conversed very much with the other guests. His first language appeared to be French, though he spoke a little English. People probably remembered seeing the man with a dog. The dog was fairly large but appeared friendly and seemed to dote on its owner.

Right now, the “Frenchman” had a room at the Red Lion, though some might have recognized him from Madame Filette Flemming’s French boarding house, at 129 S. 2nd St., where he had stayed when he first arrived in the city. While he was at Madame Flemmings, a strange occurrence took place, according to a person who was later interviewed by the police. When the acquaintance came to visit the young man in his room, the man jumped out the window. It was surmised that he had mistaken his visitor for a police officer.

Some people no doubt remembered the young man as a frequent visitor to Hansell’s clock and watch shop up the street. The young customer had carefully browsed through some of the merchandize—but bought nothing. On his visits, however, the man was particularly attentive to Hansell’s dog, which the watchmaker had brought to the shop to serve as a nighttime guard dog. After a while, the young man asked if he could buy the dog from Hansell, and since the animal and the young man appeared to have bonded quite closely, Hansell accepted (Paulson’s American Daily Advertiser, July 3, 1826).

Evidently, the man moved his quarters to the Red Lion soon after his first visit to Hansell’s. From that nearby location, he might have better ascertained when the shop would be closed and when the local watchman would be making his rounds.

On this Saturday night, after the taverns had largely emptied out, there were few people to be seen on Market Street. Yet one malingerer had mischief in mind. Somebody broke the window of the shop owned by W.H.C. Riggs, a clock and watchmaker at 112 Market St., reached in, and took a small amount of finger rings, lockets, and other jewelry that was on display. (Even today, a “ghost” sign advertising Riggs’s shop is still engraved in the sidewalk in front of 310 Market St. A colorful statue of a mariner using a sextant used to stand above the door; it is now in the Philadelphia Maritime Museum.)

Riggs’s shop was not far from the headquarters of the city watchmen, in the Old Courthouse in the center of Market St. But the culprit managed to escape without being apprehended. Where did he go? It is easy to believe that the burglar simply walked up Market St. to another watchmaker’s shop—that of James Hansell. Perhaps, in fact, the thief stopped off along the way to deposit his loot in his room at the Sign of the Red Lion before undertaking the burglary at Hansell’s showroom, sometime between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. on Sunday morning.

Entry into Hansell’s premises, however, would have required more effort than merely smashing a window. Although the watchdog had been removed, there were still no less than three locks to negotiate to get into the shop, while as many as six more locks had to be picked to gain access to most of the commodities. The most expensive items were encased inside an intricate iron chest. Yet the burglar succeeded in opening all of the locks, and breaking into all of the cabinets, without committing the slightest injury to any of the locks or doors (Philadelphia National Gazette, May 5, 1826).

The city watchman assigned to the district later reported that he had heard some banging inside the building as he passed by. But he had assumed that the noises came from James Hansell or a member of his family—no doubt working overtime on a project—and continued on his rounds.

The robber flees to New York

The young “Frenchman” soon checked out of the Red Lion and made his way to New York City. He probably left on Monday morning. Every weekday at 6 a.m., it was possible to board a coach to the New York ferry right at the door of the Red Lion. Passengers could then sail up the Delaware to Trenton. They then generally boarded another coach, which carried them to a steamboat on the Raritan River that sailed to New York. The quickest journeys took about 11 hours, which would enable the traveler to arrive at suppertime.

The following Saturday, April 21, the young man came into the shop of William B. North, a respectable jeweler and silversmith on Broadway in Manhattan and offered a number of gold watches for sale. The New York Times (April 27) reported that the shop attendant (identified in later news accounts as a Mr. Black), who was about the same age as the “Frenchman,” after examining the items, “found that they agreed with the description of some property of the kind taken from the shop of Mr. Hansell, of Philadelphia. … He contrived to keep the person in the shop until an officer was called from the Police Office, who took the property and secured the man.”

The dispatch continued, “As the property taken was of great amount, no time was lost in discovering the place of abode of the prisoner, whence a trunk was taken, containing the greater part of the stolen goods, and some articles not taken from the shop in Philadelphia.” A quantity of counterfeit St. Domingo coins was also found in the man’s pockets.

At some point, the prisoner was taken to police headquarters in Reed Street, where High Constable Hayes had his office. From there, he was quickly brought before a magistrate, where he confessed that he had already sold fourteen of the watches—six to one person and eight to another.

A couple of days later, he was brought to a magistrate for another examination. The New York American (April 28) reported: “On being questioned regarding several musical snuff boxes found in the trunk, which did not belong to Mr. Hansell, he would give no account of them.” The article went on to say that “among the articles found in the trunk was an ornamental gold repeater [pistol], which Mr. Hansell observed did not belong to him, but he had seen it before, and knew it to have belonged to a gentleman in Baltimore.”

The story that the man gave to the magistrate to explain how he had obtained the stolen goods was scarcely credible. He claimed that he had purchased the trunk and other merchandise from an Italian man he had met in the street near the Philadelphia steamboat landing. He reported that he had paid the nameless stranger $3000 for the goods—$1000 in cash and $2000 in a personal bank note.

The young man declined to say how much he had received for re-selling the fourteen watches. And when asked where he had sold them, he was unable to supply locations and refused to guide a police officer there, stating that he would not be able to find the places again. The reporter for the American remarked that the man “was in considerable tremor during the examination.”

In the interview with New York City police, the man revealed that he was 23, born in Geneva, Switzerland, and had sailed from Le Havre to New Orleans in the ship Edward about 10 months earlier.

A daring prison escape

A police officer named Azel Conklin conveyed the prisoner in chains back to Philadelphia. For Conklin, the journey was probably a welcomed out-of-town sojourn. At the time, he and two city watchmen were under indictment for assault and battery and false arrest of a man, Paul R. Jehovitch, at a New York barroom on March 28. It appeared at the trial that Jehovitch had been brutally swept up in a raid on the establishment; the cops had alleged that gambling was going on over a game of billiards. On May 9-10, Conklin and the other two were found guilty (National Gazette, May 12, 1826).

The “Frenchman” was arraigned in Philadelphia Mayor’s Court on Friday, April 28. After an examination, the mayor explained to him that he would be tried on charges of larceny at the next session of the Mayor‘s Court. This would be arranged instead of committing him to the Court of Oyer and Terminer on the more severe charge of burglary. The reason for the lesser charge, the mayor said, was because he had broken into a place of business instead of a dwelling where people slept (National Gazette, May 4, 1826).

In the meantime, the recovered goods were returned to James Hansell . It was thought that the total value of the stolen items had been about $5000, and Hansell received almost all of it back except about $400 worth (ibid.). It was not reported whether Hansell ever got his dog back.

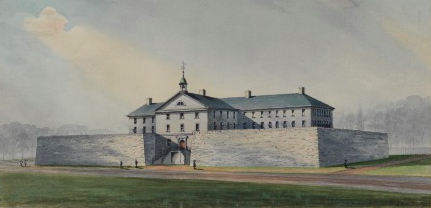

The prisoner was incarcerated in the Arch Street Prison. The facility, near the intersection of Broad and Arch Streets (close to where the Municipal Services Building is today) was designed to hold “prisoners for trial, vagrants, runaway or disorderly servants and apprentices, and all other descriptions of persons (except convicts).” And eventually, even convicted felons were sent to Arch Street because of overcrowding at the archaic Walnut Street Prison. Evidently, he languished there for well over a month, until at mid-day on Sunday, June 18, he made an incredible escape with three other men. The prisoners were able to climb up a 40-feet-high waterspout, surmount the prison wall, shimmy down the lightning rod on the other side, and then dive about 15 feet into a puddle of soft mud. The young “Frenchman” had no hat, coat, or shoes when he escaped.

One report, reprinted in the New York Evening Post (June 22, 1826), stated that about a dozen people witnessed the escape, and in fact, the prisoner landed within a few feet of an Irishman. That incident allowed the reporter to add a bit of racist humor to the episode. He commented that when asked why he did not try to apprehend the escapees or at least give the alarm, the Irishman answered, “Faith! I didn’t put ’em in at first, and how could I then?” Some readers, of course, might have asked themselves how they would have reacted if four desperate criminals landed at their feet—would they have hastened to try to apprehend them?

The “Frenchman,” now free, again made his way to New York City. Then one day, he decided to take a stroll along the Battery. But he had been over-confident. Mr. Black, the sales clerk at the jewelry shop, recognized him in the street and boldly approached. The New York Times commented, “Paul Pry*** like, he ventured to question how he could have so soon settled his former speculation, and also went so far as to tap him on the shoulder. Monsieur was about taking French leave, and aimed a blow at his assailant, when some of those rude gentry, who are almost always found at every public place … came up and once more conducted the gentleman to Brideswell,**** where he waits the orders of our Philadelphia brethren, who are desired to take better care of him for the future.”

Philadelphia’s High Constable John McLean was delegated to travel to New York to retrieve the prisoner. Accordingly, he was brought back to the city on Tuesday, July 11, and once more lodged in the Arch Street prison (National Gazette, July 15, 1826). What happened next to the errant “Frenchman” is still unclear. When I find more information, this article will be updated.

James Hansell continued in a long career as a clock and watchmaker. A tall case clock attributed to him is in the DuBarry Conference Room at the Athenaeum in Philadelphia. Another is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, and at least two others have been located. Hansell was an ardent anti-slavery abolitionist, and in 1847 ran for mayor on the Free Soil ticket (receiving all of 10 votes!). His brother Thomas was even more active as an abolitionist; he was a stockholder and manager of Pennsylvania Hall, the anti-slavery meeting place that was burnt down by a racist mob in 1835.

In June 1859, Hansell retired from the clock-making business and vacated his watch and jewelry store at 706 Market St. He died on March 31, 1865.

NOTES

* A biography of “James Hansell – Clock/Watchmaker,” by Nancy Ettensperger (2014), with many illustrations, can be found online at https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~edbradford/genealogy/ed/additional/hansell/james.pdf. I have used Ettensperger’s article as a source and highly recommend it.

** In 1883, the Declaration House and the twin building next door were torn down and replaced by the Penn National Bank building, designed by noted architect Frank Furness. The bank was demolished in the 1940s and supplanted by a one-story lunch place called Tom Thumb and a parking lot. A replica of the Declaration House was erected on the site in 1976, and is operated as a museum by the National Park Service. Details of the research on the house under the auspices of the NPS, which I have briefly summarized in this section of my article, is contained in the 1972 “Historical Structure Report, Graff House,” by John D.R. Platt at https://irma.nps.gov/.

*** “Paul Pry” was a popular farce in three acts, written in 1820 by British playwright John Poole. The name “Paul Pry” entered the English language to denote an excessively inquisitive or meddlesome person.

**** Bridewell was a generic name for penal institutions, taken from the name of the prison in London within a former royal palace. Construction of Bridewell in New York began in 1768 on the site now occupied by City Hall Park. It was completed after the Revolution and served as the city’s main prison until the Tombs was constructed in 1838.