By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

PART I — THE EARLY YEARS: A REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT

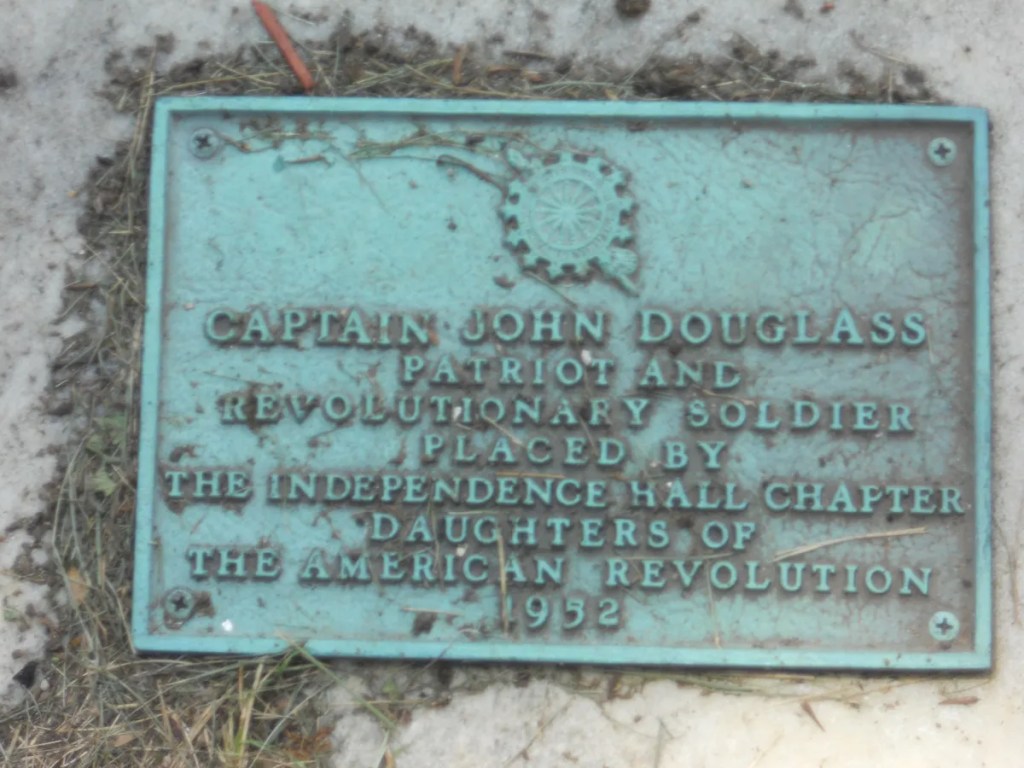

The long stone marking the grave of John Douglass Sr. lies prominently near the door to Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church in Philadelphia. Douglass died on his 94th birthday, July 8, 1840. The vice president of the United States, Richard M. Johnson, was among the close to 1000 people who attended the burial. They came to pay homage to one of the last living men who had served as an officer in the American Revolution.

During his long lifetime, John Isaac Douglass worked as a cabinet maker, and later served as a Philadelphia city alderman and as county sheriff. He was born in Philadelphia on July 8, 1746, according to most sources, including his burial records and several censuses. (1) He was the son of John Isaac Douglass and Elizabeth Crispin—both of them immigrants from London, England.

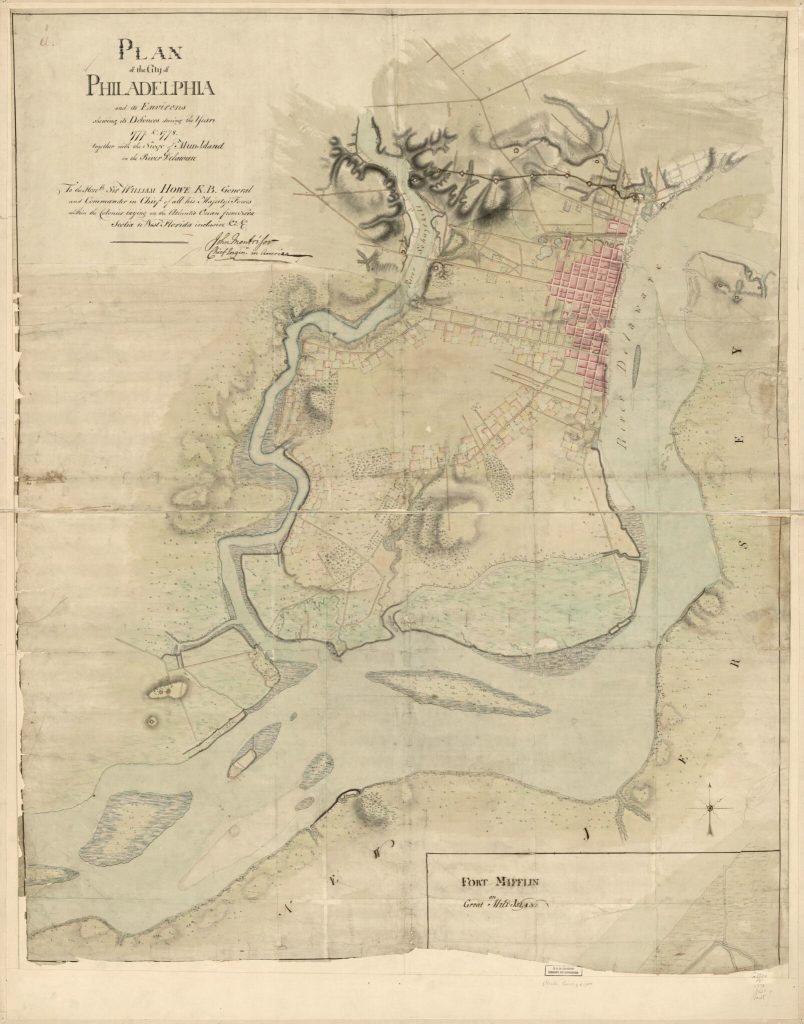

On Aug. 10, 1772, Douglass married Ann Jones (born 1749) at Christ Church. Ann was the eldest daughter of Christina (sometimes written as Christiana) and Nils Jonason—also known as Neals Johnson, Nicholas Jones, and similar names. Her father, a descendant of another Nils Jonason (1655-1735) and Christina Gästenberg (1662-1735), was a farmer and member of the vestry of Gloria Dei Church. He inherited a large tract of land in the district of Kingsessing, on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, close to the road to Darby (now Woodland Avenue) and around where the University of Pennsylvania is now located. The location of the land is clearly shown on maps of the era, such as Will McFaden’s “Plan of the City and Environs of Philadelphia,” engraved in 1777. He also owned a smaller parcel along the Schuylkill, just north of naturalist John Bartram’s land (now a public park and historic site called Bartram’s Gardens).

In the year following John’s and Ann’s marriage, on May 18, 1773, their daughter Elizabeth was born (christened on July 17, 1773, at Christ Church). Their first son, John Isaac Douglass III, was born on Feb. 16, 1774 (christened July 28, 1776) and a second son, Neals, was born in 1775. A second daughter, Christiana, was baptized at Christ Church on Dec. 18, 1776. In some biographical entries on Douglass, there is a mention of a daughter named “Catherine,” born on Oct. 9, 1776, who died seven months later. However, the name “Catharine” might have resulted from a misreading of the tombstone during the 19th century, which confused her with the actual Christiana.

It appears that Douglass began his occupation as a cabinet maker well before he married Ann. On May 11, 1772, according to Philadelphia city records, John Douglass, joiner —i.e., a skilled woodworker who specialized in joining together pieces of wood, often for furniture, cabinetry, and ornamental house fittings. (i.e., a cabinet maker)—was assigned an apprentice named John Galler for the remaining portion of his seven-year indenture, which had begun on Jan. 15, 1768.

A little more than a year later, on July 30, 1773, Galler was re-assigned. The artisan Francis Trumble took him on as an apprentice for the remaining 18 months of his indenture, in order to be “taught the art and mystery of a Windsor chair maker.” Trumble was one of the key designers of the Windsor chair in America, and in 1776 produced the chairs that were used by the Continental Congress. It would be understandable if Douglass, who was young and relatively new in the trade, had agreed to allow his apprentice to work for a portion of his indentureship with an established master of the craft in order to receive specialized training.

The record notes that Douglass was to be paid £8 in compensation for Galler’s reassignment, and that the new indenture was carried out with the consent of Galler’s brother in law, Alexander Adams—who was presumably the young man’s guardian. Adams had married Martha Galor, John’s sister, in 1764. (See: “Record of indentures of individuals bound out as apprentices, servants, etc., and of German and other redemptioners,” Oct. 3, 1771 – Oct. 5, 1773, on loan to the American Philosophical Society).

In 1774, according to tax records, Douglass paid £25 to Robert Smith, a stalwart of the Carpenters’ Company and designer of some of Philadelphia’s most important buildings of the era; he has been called “America’s most important 18th-century architect.” The purpose of Douglass’s payment to him is obscure.(2)

Another mention of John Douglass was dated June 15, 1775, when the following notice ran in the Pennsylvania Evening Post: “RAN away from the Subscriber, living in Almon-street [Almond Street], Southwark, Philadelphia, the fourteenth Instant, A SERVANT GIRL, named Mary Brine, about seventeen Years of Age, short and thick set, pleasant when talking, a little pited with the Smallpox; had on a Purple and white short Gown, green Skirt, black Bonnet, white Handkerchief, and bare-footed. Whoever takes up said Servant, and secures her in any of his Majesty’s Jails, hall have TWO DOLLARS Reward if in the City; if out of it FOUR DOLLARS, and all reasonable Charges. — JOHN DOUGLAS”

I have not found verification that our John Douglass and his family were living on Almond Street in that period, but it is not implausible since no other residents named “John Douglass” appear in the records of Philadelphia and its suburbs until the final years of the Revolution. And we know that Douglass lived in that Southwark neighborhood for many years.

“Associator” militias take up arms

By that time, 1775, the revolutionary war with Britain had already been ignited in Massachusetts. The British march on Lexington, Mass., had taken place two months earlier. Following the battle of Lexington, the Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia in May, resolved to raise an army. The clash of arms in Massachusetts further inflamed sentiment for independence in Pennsylvania, where it had been brewing for over a year. Revolutionary consciousness gained strength particularly among the poorer and “middling” classes of people—including many craftsmen and journeymen—and among small farmers in the interior. There is no doubt that John Douglass, too, was moved by this sentiment.

Meanwhile, people across the province began to form “Associators” militias—sometimes reconstituting the formations that settlers had organized in earlier years to fight attacks by Native Americans.

Even the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, which was dominated by wealthy merchants and big landowners, began to reflect the popular sentiment. On June 30, 1775, after the Quaker Party withdrew, the Assembly made a decisive shift from its earlier conservative policies. The body voted to give official recognition to the “Associators” groups, ordered that the armed volunteers coalesce into battalions, and ordered 5000 new muskets and other military equipment. By November 1775, the Assembly had approved enlisting men into a regular militia. These were some of the last acts of the Provincial Assembly, which in late June 1776 dissolved itself and was supplanted by the Pennsylvania Provincial Conference—which in its sessions in Carpenters’ Hall declared that Pennsylvania was now independent from the British Empire.

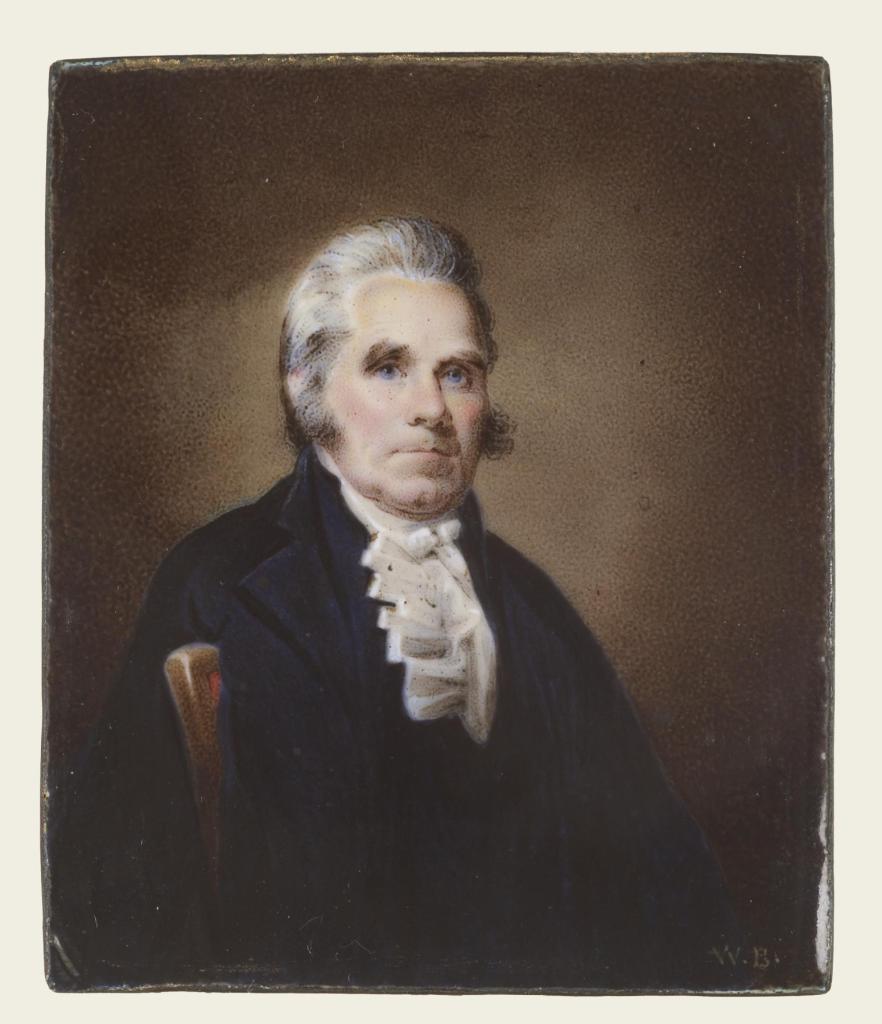

A new popular leadership soon gained prominence in Philadelphia. It consisted of radically minded men from less wealthy backgrounds who until then had been relatively unknown. They included Thomas Paine, Timothy Matlack, James Cannon, Christopher Marshall, George Bryan, Thomas Nevil, and David Rittenhouse. These men and their committees advocated not only independence from Britain but free elections by the people and a new Pennsylvania constitution. They also insisted that the Pennsylvania militia ranks should elect their own top officers. Douglass undoubtedly knew many of these revolutionaries and was influenced by them.

Douglass family tradition maintained that John Douglass had been among the first to raise a company of riflemen in the city of Philadelphia, and that he clothed and equipped the company at his own expense, selling his property to raise the money. (3) Douglass, despite his lack of prior military experience, was appointed a captain in order to head up his Pennsylvania militia company. He served in that capacity—at least unofficially—as early as May 9, 1776. That is shown by the orders that were given to Capt. Douglass on that date by Col. Timothy Matlack. (4) Matlack said to Douglass: “You and your Officers (that is Lieutenants) are hereby notified to meet the Board of Officers at the College Hall tomorrow morning 9 o’clock promptly — You are expected to give notice to your Lieutenants.”

Soon afterward, the Continental Congress resolved “that a flying camp be immediately established in the middle colonies.” They saw the “flying camp” battalions as a kind of home guard in order to defend citizens and property in case of an enemy attack. For its part, Pennsylvania was called upon to provide a force of some 6000 men in 53 battalions.

Although Douglass had already been recognized as the captain of his company of Philadelphia riflemen, a rigorous debate erupted during the following month about how the militia officers ought to be selected. A radical wing of the militia movement, constituted in the Committee of Privates within the Associators of the City and Liberties of Philadelphia, took the initiative of calling a meeting in Lancaster, Pa., which would in turn designate the top officers in Pennsylvania’s Flying Camp militia. With the approval of the Board of Officers, they put out the call for delegates, consisting of two officers and two privates from each Pennsylvania battalion, to attend the Lancaster meeting in order to choose the generals who would lead them. They pointed out that the “Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, we mean such of its Members as are not quite with us, wished to have the Appointment, but we prepared the following Protest against it, as the Whole of our Success depends on a proper Choice.” In other words, they were insisting, the militia ought to elect its own officers, and not the legislature (Daniel Cunyngham Clymer papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

A series of meetings by militia officers took place in the city of Philadelphia and in its suburbs of officers in order to elect delegates to the forthcoming assembly in Lancaster, Pa. There is a good chance that John Douglass would have attended at least one of these meetings.

A description of the June 29 gathering of officers in the city of Philadelphia was written by revolutionary leader James Cannon, who had served as the clerk of the meeting: “At a meeting of the Delegates from the several Companies in the 2nd Battalion of Philadelphia Associators, Daniel Roberdeau commander, held at James Burnrider’s School-House, agreeable to Orders for the purpose for choosing two Persons to go to Lancaster as representatives from s’d Battalion to join with the Deputies from the several Battalions thro out the Province in choosing two Brigadiers general agreeable to a late resolve of Congress … Montgomery & Poole were unanimously chosen; and are hereby authorized to meet the Delegates from the several Battalions thro-out the Province on the 4th of July next at Lancaster & there to join in the election of two Brigadiers General to command the Flying Camp to be established in the Province agreeable to the resolve of Congress for that Purpose” (Daniel Cunyngham Clymer papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

A further meeting took place at Hagerman’s Tavern on July 1, representing militia members in Philadelphia County. A note by Col. Robert Lewis of the 2nd Battalion of Philadelphia County stated, “Captn Josiah Hart & Capt Marshall Edwards were appointed by the officers of the 2nd Battalion of sd Country in their behalf to meet at Lancaster the deputies of the associators of the Province to choose two Brigadiers General” (Ibid).

The meeting of militiamen duly convened in Lancaster. John Douglass was not a delegate (attendance and voting returns from the meeting can be found among the Daniel Cuyngham Clymer papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania). However, on July 3, the delegates at Lancaster officially designated (or ratified) John Douglass as a captain in the “Flying Camp.”

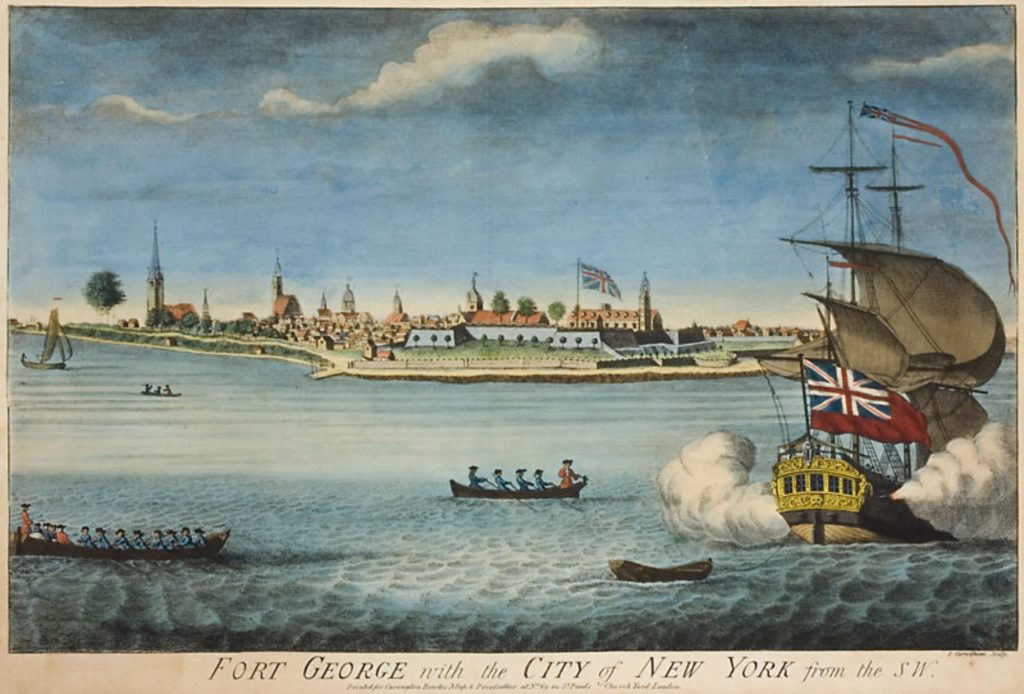

A month after the Lancaster meeting, as the British made a move to take New York City, the inexperienced Pennsylvania volunteers were marched northward to join the Continental forces in defending the city: “In Convention for the State of Pennsya, Saturday, Aug 10, 1776 — 1. Resolved, That the Commanding Officers of the several Battalions in the respective Counties of this State immediately March to New Jersey with their whole Battalion” (John Dickinson papers, Library Company of Philadelphia). Around that time, Capt. John Douglass also took his company on the road through New Jersey to New York City.

Timothy Matlack remarked on that period, but many years later—on Sept. 2, 1822—in order to verify Douglass’s participation in the early phases of the American Revolution. His note was presumably in support of Douglass’s application for a military pension. Col. Matlack affirmed that Douglass was “entitled to receive a certificate — That soon after the battle of Lexington, he joined the first Volunteer battallion [sic] of riflemen — and sometime afterward joined the Continental Army — And that the next day after the battle of Long Island [Aug. 27, 1776] I saw him in the city of New York with our retreating army.”

The defeat of the American army on Long Island initiated a period of discouragement for the Continental Army. George Washington wrote to the president of Congress in September, “Our situation is truly depressing. The check our detachment sustained on the 27th ultimo [the battle of Long Island] has dispirited too great a proportion of our troops and filled their minds with apprehension and despair. The militia, instead of calling forth their utmost efforts to a brave and manly opposition in order to repair our losses, are dismayed, intractable, and impatient to return [home]. Great numbers of them have gone off—in some instances almost by whole regiments, by half ones, and by companies at a time.”

It is understandable that the militias were melting away following the sequence of defeats. The members of many units consisted of the young men (and some old men) from entire villages—people who had known each other even before they enlisted. At the beginning, they had been inspired by idealism and patriotism—as well by as the prospects of adventure. And there is no doubt that for many poor farm hands, indentured servants, or Black slaves, the idea of running off with the army seemed liberating. But now, seeing their friends and neighbors dying in battle, with no apparent gain in the revolutionary war, gave very little to cheer about. And besides, the time for harvesting crops back home was fast approaching.

Moreover, day-to-day conditions on the battlefront were grueling. And while they were hard enough on the Continental soldiers and lower officers, living conditions for militiamen were even worse. Rations were scanty and frequently not fresh; even as late as 1780, Washington noted that men often went several days without bread or meat. Militia members usually did not wear standard uniforms; most of them had to provide their own clothes and often their own eating bowls and spoons. Some had no shoes. Many brought their own muskets, for which they were supposed to receive an extra monetary award when they enlisted. However, wage payments for the troops often came late or not at all.

A small victory on Staten Island

Occasionally, good news arrived. About six weeks after the battle of Long Island, on Oct. 15, Douglass and his company of the Flying Camp participated in a raid on an enemy garrison on Staten Island. It was a small victory within the string of disastrous defeats for Washington’s troops.

The Staten Island action was described many years later in a letter submitted soon after Douglass’s death by his son, John Douglass III, in an application to receive unpaid funds from his father’s military pension and bounty lands as part of his estate. Unfortunately, only a fragment remains of the letter in an online version at Fold3. The son wrote: “… that they marched for the town [Richmond Town], and reached it before the break of day, when General Mercer began the attack on the night of it … that they drove in the picket-guard of the enemy, who retreated; that they advanced into the town, and the Hessians went into a Church [St. Andrew’s, used as a hospital by the British], from which they fixed on them; that they forced the doors of the Church, when the Hessians threw down their arms, and to the number of one hundred were taken prisoners; that they pursued the enemy through the town, and beyond till they came near a Fort, whose drum was beating and troops turning out, when an Aid-de-Camp of General Mercer came and ordered them to retreat, which they did, to Amboy [across the narrow Arthur Kill from Staten Island]; that General Mercer covered their retreat till they were landed at Amboy, and their prisoners secured in the Court House; that some days afterwards, they marched to Fort Lee, the Head-quarters, and continued with the Army on its retreat from that Fort [in November 1776].”

We might imagine that the younger John Douglass, who was a toddler when these events took place, remembered them from stories that his father used to tell him. But the tale was largely corroborated by other accounts, including a letter to George Washington that General Mercer (the commandant of the Pennsylvania Flying Camp militia) had written from Amboy, N.J., on Oct. 16, 1776: “General Green has informed your Excelleny [sic] that a party pass’d over last night to Staten Island with a view to attack the Enemy, at the east end near the Watering Place — as we advanced towards Richmond Town information was given, that some Companies of British & Hessian Troops, were stationed there — surprising them was therefore the first object, which was effected this morning at break of day — Well disciplined Troops would have taken the whole without the loss of a man — but we took only about twenty prisoners, partly Hessians & English — eight Hessians & nine British, one of those wounded, & besides these two mortally wounded left at Richmond Town — We lost two men in the Action” (U.S. National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0437).

At the time of the skirmish on Staten Island, Douglass had already been appointed a captain in the regular Continental Army. On Sept. 26, 1776, the seated convention of the state of Pennsylvania designated Douglass a captain in the state’s regiments of the Army. A letter of that date, signed by the president of the convention, Benjamin Franklin, stated that in light of their “special Trust and Confidence in your Patriotism, Valour, Conduct, and Fidelity,” the convention “Presents, constitutes, and appoints you to be Captain of a Company of Riflemen of the City and Liberties of Philadelphia agreeable to your former appointment of the 3rd of July last in the Flying Camp for the Middle States of America, for the protection of said States against all hostile Enterprises and for the Defense and establishing of American liberty.”

John Douglass was assigned to the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Line. This unit, together with the 4th, 5th, and 8th regiments, was a section of the 2nd Pennsylvania Brigade under Col. Richard Humpton. The 11th Regiment (which Humpton personally commanded) had been formed in September 1776, and on Nov. 13., when the captains were assigned to their companies, Douglass was put in charge of Company G.

About three weeks after the Staten Island action, Douglass sent a notice to newspapers in Philadelphia alerting readers to be on the lookout for two men, presumably from the Philadelphia area, who had deserted from Company G. The desertions possibly took place while Douglass’s unit was beginning the march to Fort Lee and once again engaging the superior British army.

The Pennsylvania Journal (Nov. 20, 1776) reported: “Deserted from Captain JOHN DOUGLAS’S company on the 9th of November, one WILLIAM FULLERTON, about twenty-three years of age, five feet five or six inches high, dark complexion, wears a green coat turned up with white, and sky blue jacket and breeches, has long black hair, tied behind, and is a taylor by trade. Whoever takes up said deserter and secures him shall have three POUNDS reward;

“Deserted the same day, one GEORGE HINES, a shoemaker by trade, has a dark down look, pitted with small pox, and stoops in his walk. Had on when he deserted a hunting shirt and legings. Whoever takes up deserter shall have THREE POUNDS reward paid by JOHN DOUGLAS.”

The notice appeared in the Philadelphia papers on Nov. 20, the very day that British and Hessian troops overwhelmed Fort Lee. General Washington ordered the 2000 soldiers inside the fort to evacuate their positions to avoid capture—as had happened four days earlier to almost 3000 men at Fort Washington, on the other side of the Hudson. With the fall of the two forts, the army lost almost 150 cannon, 12,000 rounds of ammunition, and 3000 muskets.

The depleted American army was forced into retreat through New Jersey with the British on their heels. Thomas Paine, who accompanied the army, wrote, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

In early December 1776, George Washington’s army crossed the Delaware River into relative safety in Pennsylvania. Inexplicably, the British General William Howe declined to ferry his troops across the river to attack the Americans. This gave Washington the opportunity to regroup his forces; the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment with John Douglass probably joined in the rendezvous. On Christmas night and into the morning of Dec. 26, Washington re-crossed the Delaware and engineered a march on Hessian troops in Trenton, N.J. It was a reassuring victory for the American cause, though there is no report that the Pennsylvania 11th Regiment took part in the battle.

Battle on the Brandywine

In the spring of 1777, Douglass probably received word from back home that his two-year-old daughter Christiana had died on March 24. But soon afterward, happier news arrived—a new son, Abraham, had been born. It was becoming clear at the time that the British forces under General William Howe would soon make a push to take the “rebel” capital of Philadelphia. On April 9, Thomas Wharton Jr., president of the Council of Safety, sent out a warning in a broadside to the people of Philadelphia: “By the Intelligence which the Council have this Day received from General Putnam, the Enemy are in motion toward South-Amboy, and it is probable they will, once more, attempt to pass through New Jersey, and endeavour to gain Possession of the City of Philadelphia.”

Wharton’s letter noted that “this City has once been saved by the vigorous, manly Efforts of a few brave Associators, who generously stepped forward in the Defence of their Country.” It pointed out that the “Spirit of Liberty which blazed forth in the Winter Campaign [and] led you forward to a Harvest of Glory on the Hills of Princetown—The Cause is the same—and the Prize we contend for, far from losing its Lustre, is become more valuable to us by the Price which we have already paid for it.” The letter reported that Congress had proposed “to form a Camp near the City of Philadelphia, to which the Militia of Pennsylvania will, when called upon, repair.” Accordingly, the militia was exhorted to again “BE READY” (Collection, Library Company of Philadelphia).

By May 1777, new recruits and supplies had flooded into the Continental Army. Washington’s forces were able to double their ranks to about 8400 men, although due to sickness and other reasons, only about 5700 were effective for a fight. They undertook a series of small battles to harry the enemy throughout northern New Jersey and on Staten Island. Washington moved the main base of his army to the Watchung Mountains, above Bound Brook. This afforded them a natural fortress to ward off a direct attack by the British while remaining in position to both defend the Hudson Valley and to head off a march by General Howe through New Jersey to Philadelphia.

On June 11, 1777, the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment was encamped at Mt. Pleasant, N.J. John Douglass reported that his company had 33 men in camp, with 10 more back in Philadelphia (perhaps on personal leave). Douglass also stated that his company had suffered six dead and that seven men had deserted. In all, 59 men had been recruited into the company, though only 41 had actually been mustered.

In the meantime, General Washington and his officers were perplexed by the movements of Howe’s army. Washington wrote to the Chevalier Charles-François d”Annemours on June 19, “Genl Howe has lately made a very extraordinary movement. He sallied out from Brunswick on the night of the 13th instant & Marched towards Sommerset about nine miles distant, when He halted & began to fortify. By this operation He had drawn much nearer to us, and was in a tolerably commodious posture for attacking our right, which led us to conjecture this might have been his design—But all of a sudden He last night began to decamp, & with a good deal of expedition, if not precipitation, has return’d to his former position, with his right at Amboy & his left at Brunswick. this was certainly a hasty resolution, but from what motive it is not easy to determine” (National Archives, Founders Online).

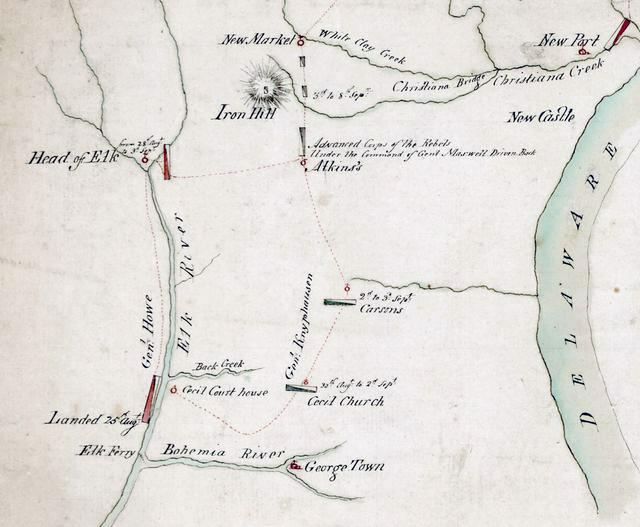

But by July, Howe’s movements became somewhat clearer. Rather than marching through New Jersey, he placed his army of some 18,000 soldiers and sailors on a fleet of over 260 vessels, which sailed from Sandy Hook, N.J., toward the south. At first, Washington and his officers thought that Howe was aiming to employ his armada for an attack on the Carolinas. Accordingly, Washington thought it would be best to order the Continental Army northward to help stop British General Burgoyne—or even to attack New York City. However, on Aug. 21, word arrived that Howe’s ships had been sighted in Chesapeake Bay. The fleet had avoided the more direct route up the Delaware River to Philadelphia, most likely because the river had been fortified by the Americans.

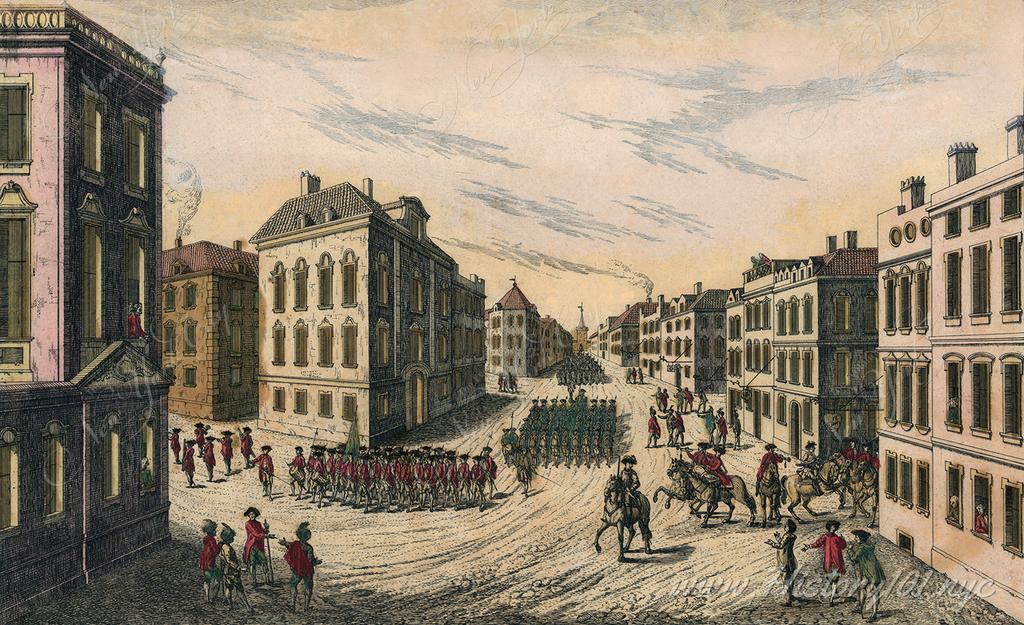

Accordingly, Washington marched his army, now increased to about 16,000, from its camp along the Neshaminy Creek to Germantown, just northwest of Philadelphia. Washington established his headquarters at the Stenton mansion, (which is still standing). On Aug. 24, they began a march down the Germantown Pike, and through Philadelphia. Over 8000 soldiers and 400 musicians took part in the parade, which took two hours as they marched in quickstep past the State House. They camped west of the city near the village of Darby, and the next day established a more permanent camp near Wilmington, Del. On Aug. 26, Washington received word that Howe’s seasick soldiers, after sailing up the Elk River, had disembarked near Head of Elk (today Elkton), Md., about two days earlier and were now moving overland.

On Sept. 3, a small clash with the British invading force took place at the Battle of Iron Hill, also known as the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, which was on a branch of Christiana Creek near Newark, Del. A section of Pennsylvania’s 11th Regiment joined with Pennsylvania and Delaware militia troops under Brigadier General William Maxwell in the attack on British and Hessian troops. After seven hours of fighting, the Americans ran low on ammunition and found it hard to resist a counter-attack by the enemy. It turned into a rout for the Americans and enabled Howe’s forces to move relatively unobstructed into Pennsylvania.

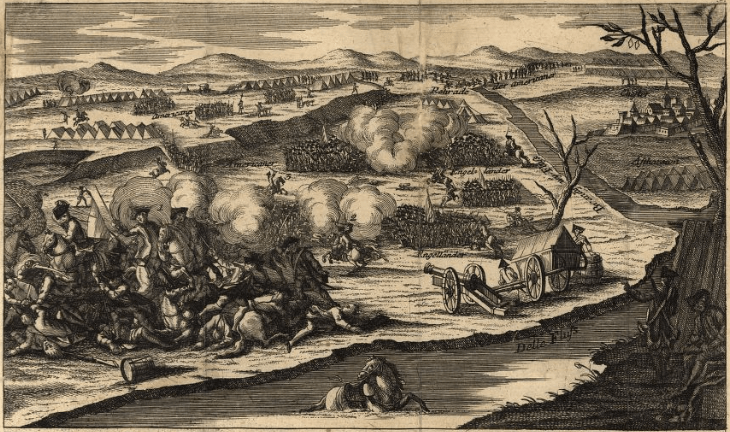

The 11th Regiment saw its first sustained action at the Battle of Brandywine, which took place a week after Iron Hill on Sept. 11, 1777. Brandywine was one of the major battles of the war, involving close to 30,000 soldiers. Washington saw the coming battle as potentially decisive; an American victory could lead to negotiations for peace. The British troops had been weakened by their long sea journey, but the Continental Army had many newly enlisted and inexperienced men and officers.

Col. Humpton’s 2nd Pennsylvania Brigade, including the 11th Regiment and Douglass’s C Company, was assigned to General “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Humpton’s units were among the troops entrusted with protecting the center of Washington’s army against the British and Hessians under General Knyphausen, who were arranged on the other side of the Brandywine Creek. The Americans were dug in at Chadd’s Ford, the major crossing point on the creek for the road east, where they waited for the British advance.

Due to faulty intelligence, however, the Americans did not realize at first that General Howe had split his forces. The major advance of the British was to the north, where they were able to cross the river at two unprotected bridges and advance in a pincer attack on the Americans. When Washington realized late in the afternoon that his right flank was threatened, he hurried to send reinforcements to the area—but it was too late for them to assume strong positions. As night approached, the Americans were forced to fall back toward Wilmington, Del.

In the meantime, the Pennsylvania 11th and other units, weakened by the withdrawal of reinforcements, saw hard fighting as Knyphausen sent his troops across the creek. The Americans suffered high casualties, even among their officers; four lieutenants were killed, and several were wounded. According to John Douglass Jr., writing in 1840, his father’s company entered battle at about 5 in the afternoon. We know that John Douglass’s men were embroiled in the thick of the fighting; for example, Jacob Hartman, a private in his company, was wounded above the knee and discharged from the army in 1779, later moving to Reading, Pa.

In the follow-up to the battle, Washington detached Wayne’s division to harass the British as they moved north toward Philadelphia. These troops, including the 11th Regiment, saw combat again at Paoli when they were caught in camp by a late-night bayonet attack. The Americans, many of them roused from sleep, fled in panic. Wayne ordered Humpton, who commanded the right wing, to move left onto high ground in order to cover their retreat. But instead, Humpton moved his troops to the right; Wayne later charged that disobeying his orders was “owing to some Neglect or Misapprehension in Colonel Humpton (which is not uncommon).” Even worse, Wayne pointed out, instead of positioning his troops behind the campfires, he ranged them in front, which silhouetted them for the British attackers. As a result, Humpton’s men suffered the heaviest losses.

Through deception, Howe was able to outflank Washington and march into Philadelphia virtually unopposed on Sept. 26. But the Continental Army had not been fully defeated. In October 1777, Washington wrote, “It was time to remind the English that an American army still existed.” He was determined to strike against the enemy before winter came on and devised a plan to mount a surprise attack against British troops at Germantown. The Pennsylvania 11th Regiment was among the troops who took part in the action. Unfortunately, the attack was begun in heavy morning fog. As the untrained Americans approached the major British lines, they advanced too rapidly and then began to fall back in confusion. At one point, Col. Humpton’s 2nd Pennsylvania Brigade, and the 11th Regiment within it—in which Douglass served—were fired on by retreating American troops, who had mistaken them for the enemy. They returned fire and then panicked in disarray. Once again, the British were the victors.

It appears that Col. Humpton’s 11th Regiment had been heavily reduced in strength due to the string of defeats at Brandywine, Paoli, and now Germantown. A return issued on Nov. 1, 1777, shows that a total of 65 rank-and-file soldiers were present and fit for duty, while 13 were sick but present, and 53 were sick and absent, with 31 on command. The numbers of men that were present were less than a third of those in camp the previous June. Capt. Douglass was recorded as present in the November 1777 accounting, but many other officers had been killed or wounded, taken prisoner, resigned, or were listed as absent without leave.

Washington withdrew his army to a temporary camp at Whitemarsh (today Fort Washington State Park). For the next three days, he engaged British troops in skirmishes; at one point units were exchanging shots across Wissahickon Creek. On Dec. 7, Howe marched out of Philadelphia, through Germantown, and then to Jenkintown. The British troops were able to rout the American forces that they met, and Howe was obviously hoping that this time his army could deal a knockout blow to Washington’s troops. However, on Dec. 8, Howe astonishingly decided to return his troops to Philadelphia—perhaps calculating that the Americans were too well dug in to make an assault worth the cost in resources and casualties.

The 11th Pennsylvania was present at Whitemarsh during the battles, but accounts state that it did not have the opportunity to participate in any military action. On Dec. 7, in the midst of the fighting at Whitemarsh, John Douglass resigned his commission, though he apparently did not leave the army immediately.

On Dec. 11, the Continental Army left Whitemarsh for its winter quarters at Valley Forge, arriving there on Dec. 19. Douglass’s son, John Jr., wrote years later that his father had accompanied the army to Valley Forge and remained there for a time with his company. And indeed, Capt. John Douglass is listed on the muster role for the Pennsylvania 11th Regiment at Valley Forge, and there are indications that he helped in procuring supplies for the troops. It appears, however, that Douglass left the Continental Army around the end of the year.

The reasons for Douglass’s resignation are not entirely clear. He might have been worn down by the string of battlefield defeats, often caused by poor leadership. He probably knew a number of men who had been casualties of those setbacks. Food was scanty, as were blankets, warm clothing, and shoes. He might also have been discouraged by the wrangling that was going on among the top officer corps. Washington himself had come under criticism for his strategic and tactical decisions; a group of senior officers and political figures associated with the “cabal” promoted by Brigadier General Thomas Conway even urged his dismissal.

But it is obvious that Douglass was also highly concerned about the welfare of his young family—especially now that the British were occupying Philadelphia. After he resigned, it is doubtful that Douglass and his family remained in Philadelphia. As a Continental officer, Douglass would have faced almost certain capture if he stayed in the city. The family might have sought refuge at Ann’s parents’ farmhouse in Kingsessing. But that was still very close to the city, and British raiding parties were scouring the farms in the area in order to confiscate crops, hay, and livestock to feed their troops. Some farmhouses, perhaps where the inhabitants had resisted, were burnt to the ground.

In fact, Nils Jonason’s farm and others along the road to Darby were in direct peril. On Dec. 22, 1777, the British General Howe crossed the Schuylkill River into Kingsessing with some 7000 troops. On that date, Major John Clark Jr., who was in charge of coordinating the Continental Army’s network of spies in the area, wrote to George Washington: “A large Body of the Enemy are on their march to Derby, where they must have arrived by this time, the number uncertain, but you may rely are formidable, they certainly mean to forage.” On the following day, he wrote to Washington that the British General Howe’s “Troops are encamped all along the Road from the [Gray’s] Ferry to the high Ground on this side Derby” (National Archives, Founders Online). Therefore, it would have been far safer for Douglass and his family to move even further into the countryside for the duration of the British occupation—which lasted until June 18, 1778.

Resuming the cabinet-making business

On Feb. 7, 1779, John and Ann Douglass’s son Joseph was born. Their daughter Ann was born on July 24, 1783, and another son, Neals, was born on April 14, 1785. The two latter children were baptized at Gloria Dei Church on Jan. 8, 1786.

Some months earlier, on Sept. 3, 1785, John and Ann Douglass went to Gloria Dei Church to attend the wedding of Ann’s youngest sister, Rebecca, who was 20 years old (born Dec. 29, 1764). Rebecca was marrying the widower George Sheed, a plasterer, who was twenty years older than she was. John Douglass gave sureties for the couple at the wedding.

In 1790, the Douglass’s daughter Elizabeth, just 17, married George Bringhurst of Germantown. Much sadder news came the same year, when John’s mother and their daughter’s namesake, Elizabeth Crispin Douglass, died. His father, however, survived for many more years.

In those years, John Douglass returned to his craft. Philadelphia tax records for 1782, made while the revolutionary war was still raging in the South, lists Douglass as a “joiner.” The following year, the tax roles list him as a cabinet maker—essentially the same as a joiner. In Francis White’s “Philadelphia Directory” for 1785, Douglass is again characterized as a cabinet maker, with his place of business on South Street (still often called by its old name, Cedar Street), between 2nd and 3rd Streets.

No street directories were issued in Philadelphia for the years 1786 to 1790. The first census of the United States, in 1790, shows Douglass as a cabinet maker, living at 76 South (Cedar) Street. There are 13 people listed in the household, including six free white males under 16 and three free white males above that age, plus four free white females of various ages.

Between 1791 and 1793, the re-issued street directory showed John Douglass’s shop remaining at 76 Cedar Street, but the family’s home address was now at 12 George Street, in the district of Southwark. That building is still standing, and the address today is 604 S. American Street (see photo).

Earlier, in May 1782, Douglass had acquired a large plot of property at the corner of South and George Streets from the brewer Luke Morris. That property adjoined his house on George Street to the north.

On May 23, 1794, Douglass acquired another plot of ground adjoining his property on George Street to the south. That ground, which ran all the way back to Third Street, contained a brick kitchen but no other buildings. The property had been owned by a mariner named John Robertson (alias “Robinson”), who died in 1786; it had been inherited by Robertson’s widow, Ann, and their five surviving children, who agreed to sell it to Douglass.

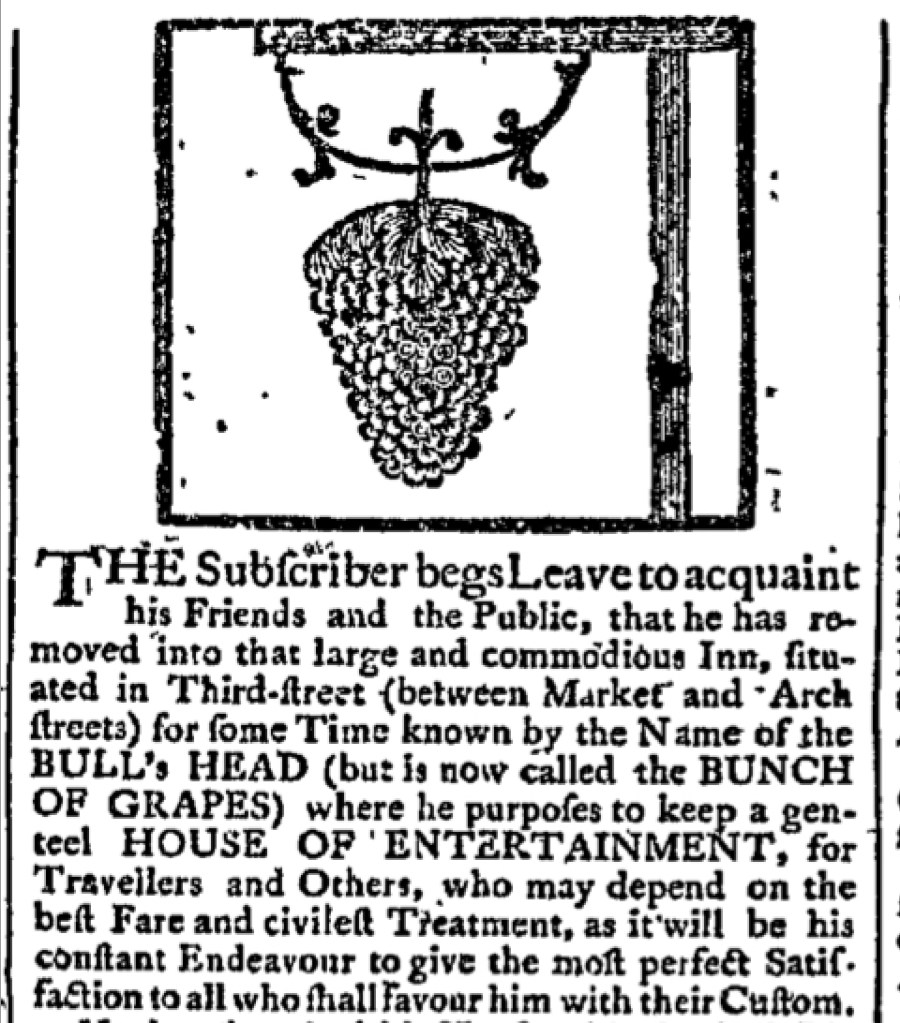

Also in 1794, at some point following the abatement of the yellow fever epidemic during the previous autumn, Douglass moved his shop to Dock Street, at the corner of 2nd Street. That section of Dock Street served as a food market and was known at the time as Farmers’ Row; the section immediately to the north served as a cattle market. Dock Street had been created after the fetid Dock Creek was declared a public nuisance, diverted into a sewer, and covered over; that portion of the creek had been covered less than a decade earlier. Douglass also maintained an address for his business at 67 Walnut Street, at the corner of Second. Since this was the same intersection that was shared with the Dock Street premises, it seems to indicate that he had one shop with doors on adjoining streets.

Building houses on Powell (Delancey) Street

On May 2, 1796, John Douglass was certified as a commissioner of the Southwark District—perhaps his first foray into political office. Later that year, he collaborated with master house carpenter Benjamin Thornton to construct two 3 1/2-story brick houses at 23 and 25 Powell Street, west of Fifth Street. On Nov. 2 of that year, Douglass and Thornton purchased the lots jointly from Samuel Emlen Jr., who had been granted the land from his father. It was a huge lot, stretching 94 feet along Powell Street and 119 feet in depth.

The deed (D 69, p. 178) specified that Douglass and Thornton “shall and will from the date of these presents erect, build, and finish or cause to be on their Powell Street Front of the hereby granted lot two good three Story Brick Houses, each of them to be not less than fifteen Feet and a half in front by thirty feet in Depth.” The deed added: “And shall and will within the space of three Years from the Date hereof erect, build and finish or cause so to be so many more good three Story Brick Houses on the said Powell Street front of the hereby granted Lot of Ground as will fill up and Occupy the remainder of the front of the said hereby granted Lot of Ground …”

Although the street name and numbering changed over the years, the houses remain standing at 519 and 521 Delancey Street. It does not appear that Douglass and his family ever lived in either of the houses; instead, they were rented to tenants. According to the 1798 tax lists, Douglass rented 15 Powell Street, which might be one of the same properties, to French immigrants. At the same time, his partner Benjamin Thornton (or his estate) was taxed for ownership of the still unoccupied property on Powell Street. Benjamin Thornton died on Jan. 2, 1798. The newspapers reported that death came “after a long and lingering illness.” In his will, John Douglass and the widow, Rebecca Thornton, were designated joint executors of his estate.

A few weeks after Thornton died, on Feb. 6, 1798, Douglass sold an unbuilt portion of the Powell Street property (525 Delancey Street today) to the noted house carpenter and architect Owen Biddle Jr., who constructed a house there that was taller, roomier, and much more stylish than Douglass’s and Thornton’s buildings (see Deed D 74, p. 177). Soon afterward, Douglass sold the property next to it (now 523 Delancey Street) to Joseph Cowgill, who partnered with Biddle. The adjoining houses were erected at the same time in similar styles. (Cowkill’s house is slightly taller than Biddle’s; the third floor might have been raised in height later in the 19th century.) In 1805, Biddle published his book, “The Young Carpenter’s Assistant,” but the following year, his promising career was cut off when he died at age 32.

Much later, in 1815, Douglass purchased additional property on Powell Street, where his family took up residence (deed book MR 11, p. 336).

In the year before Thornton’s death, Douglass had moved his shop to a building he purchased at 186 S. Second Street and advertised himself as a cabinet and chair maker. The premises were three houses above Pine Street and close to the well-trafficked New Market shopping district. The building was probably already adapted to Douglass’s needs. It had served as Francis Trumble’s chair-making shop until his death in 1791. Subsequently, from 1793 to 1796, it was the workshop of Jacob Cozens, a cabinet maker, from 1793 to 1796.(5)

Douglass is shown on 1798 tax lists as also owning farmland and a frame house located on the road to Darby on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, near Gray’s Ferry. This was obviously a portion of Nicholas Jones’s land, which was left to his daughter Ann Douglass at his death. At the same time, George Sheed owned a nearby tract of land, which apparently had been left to his wife Rebecca, Ann’s sister. John Douglass also owned a rental property between Lombard and Gaskill Street; the front of the house was rented to a Widow Moseley, while the back portion was rented to John Hargesheimer.

When Douglass opened his shop on Second Street, his son, John Jr. established his own cabinet-making enterprise at the former shop at 67 Walnut Street and remained there for two or three years. In the directory for 1801, the younger John Douglass is shown with his shop at 186 Second Street, while his father is on South Street—perhaps at the same premises that he had occupied some 15 years earlier. However, in 1802, the locations are reversed, with John Jr. operating the workshop at 86 Cedar (South) Street, and John Sr. on Second Street. One can only conclude that the Douglasses conducted their cabinet-making enterprise in those years as a kind of partnership at both locations—at least until 1803, when the cabinet-making business appears to have been left exclusively to Douglass Junior. After John Senior entered politics that year, directories showed his eldest son once again at 186 Second Street.

PART II — A PHILADELPHIA POLITICIAN

Douglass is appointed as a city alderman

On May 22, 1802, Gov. Thomas McKean appointed the elder John Douglass to a position as Philadelphia alderman. Douglass replaced John Jennings, who had served as an alderman for the past seven years.

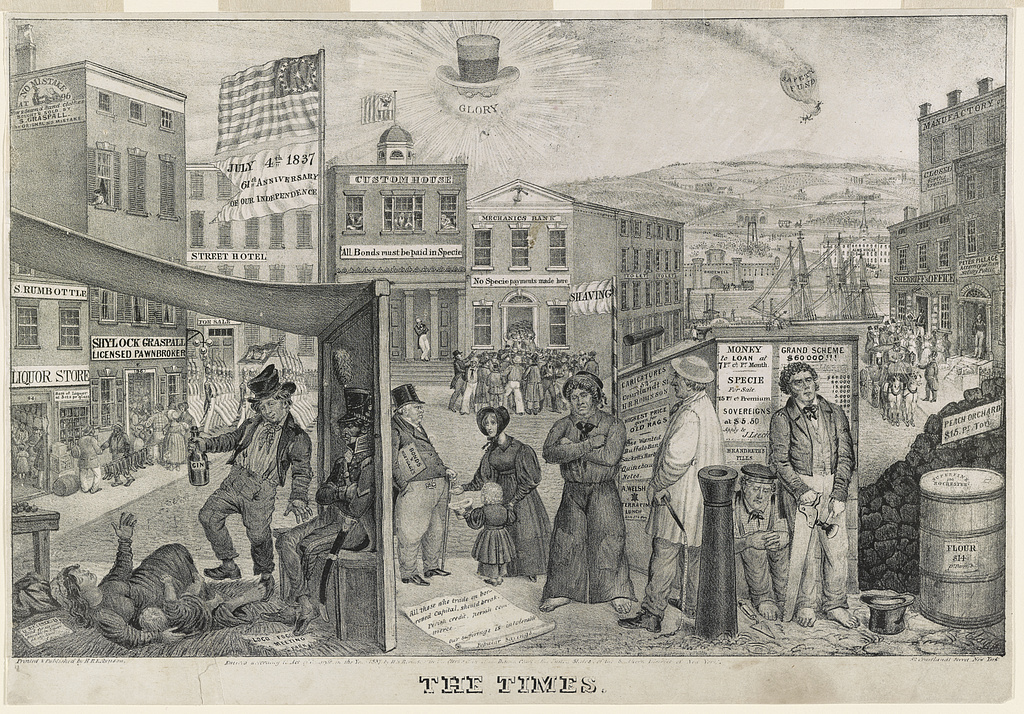

Aldermen were a group of 15 city officials who were appointed by the governor and functioned chiefly as magistrates, although they had some functions in making appointments, determining taxes and assessments, and in legislative matters. The aldermen were a carry-over from the old colonial-era government, but by 1803, when Douglass took office, aldermen had experienced a decline in powers, while the mayor, city councils, and executive officers took on more central roles in policy. The members of the Select and Common city councils (the two legislative branches of city government) elected the mayor from among the aldermen. Two aldermen served on Philadelphia’s city councils, while three of them convened the Alderman’s Court. The aldermen supposedly heard cases when the debt or demand was of an amount over 40 shillings but less than £10, though some of their cases, such as those involving claims over slaves, probably exceeded those figures.

When he appointed Douglass, Gov. McKean had elevated to office a fellow supporter of the ascendant Democratic-Republican Party (often called simply the “Republicans” and derived from the “Anti-Federalist” formation that had been founded in the 1790s by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison). Although McKean was often mocked in the rival Federalist press as being a wild-eyed “Jacobin,” his views were relatively conservative. In fact, in the next election, in 1805, McKean returned to the Federalist Party.

In July 1803, Douglass signed a letter with other Philadelphia supporters of the Democratic-Republican Party that was addressed to President Thomas Jefferson. The militia leader and radical (“Jacobin”) member of the Select Council, George Bartram, Jr. (1767-1840), had penned the letter, and it was circulated for signatures at a general meeting of the Philadelphia ward committees. The only other alderman to sign the letter was John Barker (1746-1818), who had served as a general in the Pennsylvania militia during the Revolution, was twice elected sheriff, and was elected mayor of Philadelphia in 1808.

The main subject matter of the letter dealt with the urgency, as they saw it, to remove Federalists “and other enemies of Representative Government” from public office—a policy that Gov. McKean already had been pursuing. Though McKean sought cooperation with his political opponents in state government, he saw the replacement of Federalists in office with Republicans as “cleansing the Augean stable,” as he expressed it in a June 20, 1800, letter to John Dickinson (McKean Papers III, p. 46, Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

The signers began by declaring that their views and actions had been “misrepresented” in previous communications that had been sent to the president. They assured Jefferson that “our confidence in you, testified on so many occasions has never abated.” Further on, they professed, “Knowing that you act from the purest views, feeling the happy result of your wise administration, we wish not our prospects of progressive prosperity to be over clouded by a policy which may tend to paralize [sic] the efforts of the Friends of the administration.”

At the same time, they blasted their opponents in the Federalist Party as schemers and slanderers. And they pointed out that although the Federalists were now the minority party, they had support from wealthy commercial and banking interests: “The same intolerant spirit governs the federal officers in this section of the union, which has ever been characteristick [sic] of their party; their official influence is exerted to excite prejudices against the administration; their official expenditures to purchase proselytes to their cause. …

“We look, Sir, to an election fast approaching when our whole strength must of necessity be exerted. Our opponents have already commenced their operations, and are maturing their plans of hostility and intrigue. It behoves us therefore not to stand indifferent spectators. We pledge ourselves to be calm, firm, and collected, and we look up to you, Sir, for that aid which a good cause requires, to enable us to resist the combination of Mercantile & Banking influence, which cooperating with that of men in office, menaces us with an opposition which tho’ formidable, is not such as to dismay if we continue united & receive that support from the General Government which it is in their power to afford, & which the people confidently hope for and expect.

They concluded: “We address you, Sir, with the Independence & unreserve of Freemen, under a sincere conviction of the necessity of making you acquainted with the truth, believing, that a continuance of the power to do good must depend much on the removal from office of men, who abuse the power entrusted to them & pursue their incurable propensity to do mischief, assuring you at the same time of our belief that there would be no occasion for this procedure, if you had been faithfully and correctly informed of the sentiments of the people of Pennsylvania.”

According to the notes about the letter on the “Founders Online” website, published by the National Archives, Thomas Jefferson “received this address reluctantly,” although it had been sent by supporters of his own political party. Jefferson wrote to Albert Gallatin soon afterward: ‘I hope those of Philadelphia will not address on the subject of removals. it would be a delicate operation indeed.’”

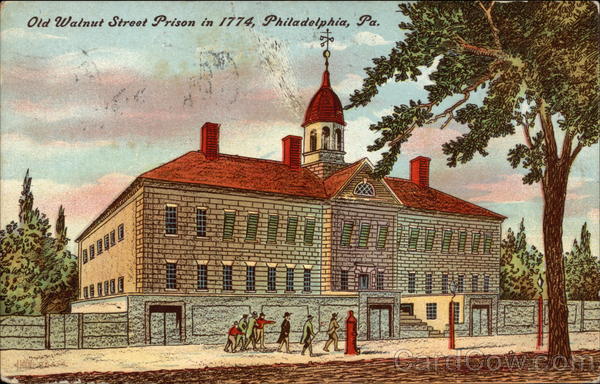

Controversy over appointment of prison inspectors

At the end of 1803, Douglass became embroiled in bitter controversy after he had been appointed as an inspector of the city and county prisons. The dispute reflected the dispute between Federalists and Republicans concerning the system of patronage—placing partisan supporters in public office—that had become common.

In December of that year, the state attorney general brought Douglass and other newly appointed inspectors to court “to show cause why an information in nature of a quo warranto [“by what warrant?”] should not be filed against them to inquire by what authority they exercised the office of of inspectors of the prison of the city and county of Philadelphia.”

Several aldermen and justices of the peace, including supporters of the Federalist Party, claimed that they had been wrongfully excluded from participating in the appointment of the inspectors. Also mentioned as an injustice was the fact that John Douglass was one of only two aldermen who did attend the meeting in which appointments were made, and that consequently, he managed to get appointed as an inspector. Thus, it was alleged, there was a conflict of interest—if not outright corruption in the process. The case was heard by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in December 1803.

In testimony before the court on Dec. 5, the banker Clement Stocker, who had been serving as an alderman, stated that when he had asked the mayor, Matthew Lawler (1755-1831), a supporter of the Democratic-Republican Party, about the date and location of the upcoming meeting to select inspectors, the mayor was evasive in giving him a clear answer. Stocker told the court that he had called on the mayor on Nov. 5 and pointed out that as an alderman he had the legal right to be present at the election. But to his inquiries about the time, the mayor merely replied, ‘The law points out the time.’”

Then “this deponent said—‘I believe it is on Monday next;’—The mayor replied ’yes.’ The deponent then inquired of the said mayor ‘at what place do you hold the election’? To which the mayor answered that he had not made up his mind.”

Stocker continued, “This deponent then addressed the mayor and said: ‘You will have no objection to let me know the time and place of the said election, if I shall call on you on Monday morning.’ The mayor replied, ‘I shall summon as many as the law directs, but I shall not let you know.’”

It was maintained in court that John Douglass was present during the foregoing conversation, but Stocker denied it.

A justice of the peace, Ebenezer Ferguson, next testified that he too was present at the Nov. 5 meeting with the mayor, and repeated the charges that Mayor Lawler had “declined to give the information desired.” Furthermore, it was reported in the press that Ferguson said that “on the day appointed by law for holding the said election of inspectors of the prison,” Monday, Nov. 7, he visited the mayor’s office a few minutes after 9 a.m. He was accompanied by a number of other justices and alderman (including Stocker and Alexander Todd). However, “the said mayor replied that the appointment of inspectors was already made.”

Alexander Tod, an alderman and former Court of Common Pleas justice, explained to the court that although previous mayors had generally summoned as many as 11 or even 13 of the aldermen, representing the various city districts, to be present at elections for prison inspectors, the law said that only two alderman were required to be present, along with two justices of the peace, in order to indicate their concurrence with the mayor’s choice.

Chief Constable and tavern owner John Millar was then sworn in. He testified that the mayor had met early on the morning of Nov. 7 at his establishment, the Mulberry Tree tavern in N. Fourth Street (between Race and Vine), with aldermen John Douglass and John Barker and with justices Frederick Wolbert and John Kesler. Millar said that “this deponent understood from them, immediately after the meeting broke up, that they had appointed Alexander Cook in the place of Thomas Leiper, and that they had reappointed John Douglass, William Binder, Jacob Heiberger, Leonard Kehmele and Paul Cox.”

Thomas Leiper, a noted banker and tobacco exporter, was a staunch Democratic-Republican; so his being replaced by Alexander Cook (also a Republican) does not seem to have been an action taken on strict party lines. It might, however, to have reflected fissures that were developing within the Republican leadership.

Edward Burd (1749-1833), an attorney and protonotary (chief clerk) of the state Supreme Court since 1778, summed up the threads of the case. He pointed out that the mayor’s action in meeting with only two aldermen and two justices, while excluding the others, was not illegal since the law provides that only a minimum number of two is necessary to be present. However, he said, the mayor’s conduct appeared capricious and disrespectful. The newspapers quoted Burd as affirming that after the other officers had presented themselves to give advice in the business of appointing the inspectors, “it was the duty of the mayor to receive them.”

Burd also called attention to Mayor Lawler’s action in diverting the place of the meeting from its usual site (the mayor’s offices) to a tavern. And he criticize the action of the mayor in scheduling the “secret” meeting “at the earliest hour of in the morning” rather than at the usual time. “There is a certain want of confidence in the measure,” he said, “betrayed by executing it at this untimely moment, which is the heaviest censure that can be passed upon it.”

On the other hand, Burd said, it had to be admitted that this was an appointment entrusted to the mayor, and not a public election. Moreover, the time and place of the appointment were not specified by the law. And so, even if the proceedings were secretive, they were not illegal. After summing up several more arguments by attorneys, Burd left the case in the hands of the judges, who announced that they would take it under advisement.

In January 1804, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued its verdict in the prison inspectors case. Judges Yeates, Smith, and Brackenridge stated that the two former of them (the majority) were of the opinion that the selection of inspectors had been illegal. They cited the grounds that the legislature had invested the mayor with a discretion that he ought to have exercised in a legal and proper manner; instead he had operated in an arbitrary, partial, and illegal manner. It was also illegal in that one of the men who was appointed [John Douglass] had functioned as one of the electors. Judge Brackenridge dissented on the first points but agreed that Douglass’s appointment was illegal (True American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, Jan. 2, 1804).

Despite the court ruling, the public controversy around the appointment of the prison inspectors dragged on for months. On April 13, 1804, The Aurora, a Democratic-Republican aligned newspaper, reported: “In the argument before the supreme court on the motion to file an information in nature of quo warranto against the inspectors of the prison—one reason mentioned as justification of the measure was that the inspectors were inattentive, or ignorant of their duty, and that the prison was in a shamefully neglected state—this idea has been propagated with much industry throughout the city and county.”

The Aurora went on to say that “it is very evident the proceedings against the inspectors of the prison originated in party and personal motives only—a decided hostility has been manifested by a former mayor and some justices of the peace of high toned federal [i.e., Federal Party] sentiments against the present republican [Democratic-Republican Party] mayor and against the corporation generally.”

As against the allegations that the inspectors were incapable of performing their duties, The Aurora published a report by the grand jury for the Mayor’s Court. To emphasize its objectivity, the publication noted that the grand jury consisted of only four Republicans while 12 were Federalists. The report stated: “The grand jury for the mayor’s court have this day [March 31, 1804] visited the jaol for the city and county of Philadelphia, and have great satisfaction in reporting to the said hon. court that they found every arrangement as to the order and employment of the persons confined, and the clean, and even neat state of the apartments, such as to merit high commendation.” It is not clear, however, whether Douglass had already been removed from his post as prison inspector.

Duties as an alderman

While the case about the prison inspectors was still tied up in court and raging in the press, John Douglass carried out the mundane tasks of his new office as alderman. In February 1803, for example, he advertised that he had in his office, at 111 Pine Street, several articles that were alleged to have been stolen. They included a spinning wheel, a child’s red jockey cap, and a blue cloth great coat. Douglass invited the owners of the articles to view them and submit a claim (The Aurora, Feb. 23, 1803).

On May 27, Douglass posted a notice that he had more items on view at his office that had possibly been stolen. The list included a pair of andirons with brass tops, a brass wash kettle, a tin coffee pot, an iron sauce pan, a pair of tongs with brass tops, a pair of brass candlesticks, and a cedar wash tub (Aurora, May 27, 1803).

A number of cases before Douglass had to do with domestic violence. For example, the Democratic Press reported (Feb. 8, 1810) on the case of Commonwealth v. John Kane: “Assault and Battery on Thomas Daniels, with an intent to murder.” The newspaper commented, “This was one of those numerous case arising out of mutual criminations and recriminations between man and wife, and which a little forbearance of either party might prevent.

“The defendant had come home with his trowsers wet, and his wife was cross to him; business at this time was slack and they began to quarrel. The wife sent fo rthe prosecutor Thomas Daniel, who came to her assistance; when Daniels came in, the defendant dodged (as the witness emphatically expressed it) a penknife he held in his hand, into the ribs of Daniels, upon which Daniels took him into the street, and after giving him some gentle castigation, carried him to alderman Douglass’s office.” We might presume that Douglass viewed the attempted murder case as being outside his jurisdiction and that he remanded to case to the higher Commonwealth Court.

Douglass is embroiled in partisan politics

In the meantime, Douglass was active in party meetings of the Democratic-Republican Party. For example, in June 1803, he chaired a public meeting of the party in New Market ward (Aurora, June 20, 1803). As a Republican activist, Douglass received his share of opprobrium from the Federalist press. In August 1803, The Tickler, a newspaper that tried to be sardonic in its commentary, wrote this about him: “We have been frequently induced to express our admiration of the learning and intelligence of both the great and little men of the Jacobin party; and when governour McKean thought proper to appoint JOHN DOUGLASS, Esq. an alderman of the city of Philadelphia, we were free in our praise of his talents and erudition.

“The following official note from the hand of Mr. ALDERMAN DOUGLASS will shew, that our sentiments respecting that gentlemen were correct. We copy it exactly as it was written, except the omission of the names. The original is left a this office, and may be seen by any person wishing to view a specimen of Mr. D’s acquaintance with the rules of English Grammar:

“Mr ***** you will Appeair at Eight oclok to Morrow morning the 31 August AS ***** ***** Denies of Ever Reeving the monney for your Debt the Execushon will Be Stopt til you Appeair — JOHN DOUGLASS”

Of course, the note might have been drafted by a clerk rather than by Douglass himself, but the poor spelling of an official message under his name must have been embarrassing for Douglass—if the claim by The Tickler was in fact truthful.

Around that time, dissension broke out into the open within the Republican Party, both in Philadelphia and statewide. The tensions had been brewing at least since Sept. 21, 1802, when a meeting of dissidents in rural Philadelphia County took place at the Rising Sun Tavern (formerly located at the intersection of Rising Sun Avenue, Germantown Avenue, and Old York Road). According to Thomas Leiper, in a Sept. 19 letter to President Jefferson, “the meetting [sic] at the Rising Sun on the 21st. has nothing in View but to turn [local Republican leader Michael] Lieb out of the Ticket for member of Congress” (National Archives, Founders Online). But the momentum continued to build after the Rising Sun meeting, and perhaps went further than Republicans like Leiper had intended.

In October 1803, the minority faction in the party opposed several Republican candidacies, including that of John Barker for county sheriff. The Aurora stated in a polemic against the “Rising Sun” faction two years later, “This opposition to Mr. Barker will fully establish in your minds the assurance that we have among us a party opposed to principle, for there was ‘no reasonable ground of objection’ even hinted—the sole object of opposition in the city was to have a rising sun man in the county elected” (Aurora, Sept. 5, 1805).

Another meeting of Republican dissidents took place on May 14, 1804 at the Harp and Eagle tavern, a “German Democratic” establishment on Third Street below Arch. It was noted in the newspapers that a number of people from the Rising Sun faction were present at the session, although they were not the majority (see the Philadelphia Evening Post, June 11, 1804). The Aurora newspaper, published by the local Democratic-Republican Party leader William Duane, denounced the Harp and Eagle meeting as being called “in secret” with the objective of opposing democratic “free enquiry” (see Aurora, June 15, 1804).

Then, on March 4, 1805, a grouping of Republicans met at the White Horse tavern in Philadelphia to celebrate Thomas Jefferson’s second inauguration and to discuss future plans. Ten days later, they published a proposal to constitute “The Society of Constitutional Republicans,” an incipient third party (The Freeman’s Journal, March 14, 1805). The Constitutionalists stood for upholding the current Pennsylvania constitution (which had supplanted the more radical 1776 constitution), as against the effort of the “Jacobins” to call a new constitutional convention. The Aurora and its publisher, William Duane—who headed the the more radical and populist “Jacobin” wing of the party in Philadelphia—reviled the new party formation and labeled it the “Quids,” a name that had also been applied to dissident Republican groupings in other states. The Constitutional Republicans, for their part, accepted the “Quids” moniker with pride.

The Quids in Pennsylvania were generally more conservative than the mainstream of Republicans and represented a somewhat wealthier class of people. But their political outlook does not appear to have been well defined. In addition to the controversy over the constitution, they supported Governor McKean and quarreled with the Republicans over the patronage policies of the governor and proposed reforms to the judiciary and the militia. In addition, they chafed over what they saw as the top-down leadership of the Republican Party in Philadelphia under Duane and Michael Leib, a leader of the German-American community and the Republican candidate for U.S. Congress in 1802 and 1804. Much of the wrangling with Duane and the party majority seems to have involved personal ambitions and rivalries in the selection of candidates for public office.

John Douglass’s political views are not entirely clear; I’ve not yet found any document that he had written to explain them. In the early years of the American Revolution, he appears to have associated with men like Timothy Matlack, a leader of the more radical and democratic-minded faction of the pro-independence forces. But three decades later, Douglass was hardly a “Jacobin.” He remained a supporter of Gov. McKean and went over to the new, more moderate party.

It is uncertain whether Douglass was present at the May 1804 meeting at the Harp and Eagle, but his break with the mainstream Republicans appears to have taken place soon afterward. Even in June 1804, he was still identified at public meetings as an active supporter of the Democratic Republican Party. However, later that summer, the Aurora printed a commentary that placed him with the opposition grouping, the Quids. The letter, by someone named “RAP PRIMUS,” stated: “It is really laughable to see how out of sorts those tertium quid men are, and the total derangement that is hourly taking place among those wise acres. … A few of the disciples of Tench Coxe may be found almost regularly every evening, making their arrangements at the house of the Man of Bark, not very far from the corner of Union and Third streets, where Sammy Carver, the would be assembly man, and John Douglass, the would be mayor, are constantly on the fidgets” (Aurora for the Country, Sept. 3, 1804). Tench Coxe, it should be pointed out, was the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Treasury who had been a noted Federalist in the 1790s, then bolted to the Democratic Republicans, and now served as one of the major leaders of the Constitutionalists in Pennsylvania.

The Republicans kept up their attack on those whom it termed “malcontents.” In June of the next year, a long newspaper commentary by the “Society of the Friends of the People,” a group of Republicans organized to support Snyder in the election, denounced John Douglass, Samuel Carver, and a number of other “constitutional republicans,” recalling that they had supported the letter that was intended to be sent to President Jefferson in July 1803, which we mentioned above (Aurora, June 17, 1805). Of course, in July 1803, Douglass and the others were still in the majority wing of the Democratic-Republican Party.

In the 1805 elections, the Constitutional Republicans formed a bloc with the Federalist Party to back McKean once again as governor. McKean, in the meantime, had switched parties and was running as the Federalist candidate, while the mainstream Republicans supported Simon Snyder. McKean subsequently won reelection over Snyder.

It must have been evident to many that Douglass was ambitious. Perhaps that’s why he became a ready target of the oppositional press. In 1803, when young Abraham Douglass was appointed as clerk of the office of aldermen, newspaper articles noted that he was the son of “Squire Douglass.” And in 1805, when John Jr. was appointed to city office, the following notice appeared in The Commonwealth (Dec. 4, 1805): Appointments by the Governor: JOHN DOUGLASS, Junr. (son of the learned Alderman Douglass, the would-be “MARE” of Philadelphia) Inspector and Measurer of Lumber, for the port of Philadelphia.” It is interesting in itself that a cabinet maker, who is a frequent purchaser of lumber, would now be put in charge of inspecting lumber at the docks (and helping to determine prices?). But the editors could not resist also poking fun at his father, who evidently made no secret of his hopes to be chosen as mayor.

Douglass continued as a target of the Republican press in the following year. The Aurora of Sept. 17, 1806, reprinted an order that Douglass had written: “To the constable of Newmarket ward or to the next most convenient constable of the said city, Greeting:

“YOU are hereby commanded to arrest the body of a man to be shewn to the Constable and bring him before me, one of the Aldermen of the said city, forthwith on the service hereof, to answer Augustin Gigg on complaint on oath of Committing an assault and Battrey on him a plea of debt or demand not exceeding One Hundred Dollars.

“Given under my Hand and Seal, this 22 day of April in the year of our Lord 1806. JOHN DOUGLASS.”

The commentator in the Aurora, using the name NO MARE (i.e., “No Mayor,”) made several observations concerning Douglass’s letter of five months earlier:

“From the face of this warrant it appears—

- That a constable was authorised by an alderman to go into the street and arrest any person who might be pointed out to him.

- “That any person thus seized was to answer, not to the commonwealth, but to Mr. Augustin Gigg—who, no doubt, might have been an injured man, but who was neither the law nor the commonwealth.

- “That an alderman undertook to exercise a jurisdiction, which the law of the land does not invest him with.

- “That he assumed by that warrant, the power and authority to hear, to try, and determine actions of trespass vi et armis, and thereupon to award damages not exceeding one hundred dollars.”

NO MARE concluded that Douglass’s order to a constable to arrest a man on charges of assault and battery was “an abuse of power … contrary to law” and therefore a misdemeanor.

A month later, on Oct. 20, the Aurora returned to its attacks on Douglass. This time, the charges were even more egregious: “On Saturday evening John Hart, the high constable, and Frederick Burkhart, another of the constables of this city, without any warrant or legal authority, and in defiance of law and the constitutional right of suffrage, went to the house of a nephew of Mr. Piper, one of the judges of the election in the Northern Liberties and who lives in Callowhill street, and by threats and menaces forced him into the city, to the White Horse tavern in Market street, before a mock tribunal, the noated [sic] alderman John Douglass presiding. They endeavored to intimidate the citizen to take an oath, of what nature we have not yet heard—but which he, with the spirit and resolution of a freeman refused and was therefore dismissed.” The article goes on to report that the constables returned to the house of the nephew at nine in the evening, but he was not at home.

And so, this time Douglass, a city official, was accused of having conspired with top law-enforcement agents to kidnap the nephew of an election official, drag him into a tavern and force him to take ”an oath”—which he refused to do. The charges, if they were proven, could show malfeasance, but the account fails to transcend mere hearsay. Why would the high constable and an elected city alderman risk their careers by resorting to mafia-style threats against a private citizen—and in a public tavern, no less, where they could be observed? What was the nature of the “oath” that they sought to extract from their victim? And who was the “nephew” whom they intimidated?

Douglass might have been ambitious, and perhaps even arrogant. But in these articles, Duane and the Aurora do not appear to have nailed him very convincingly.

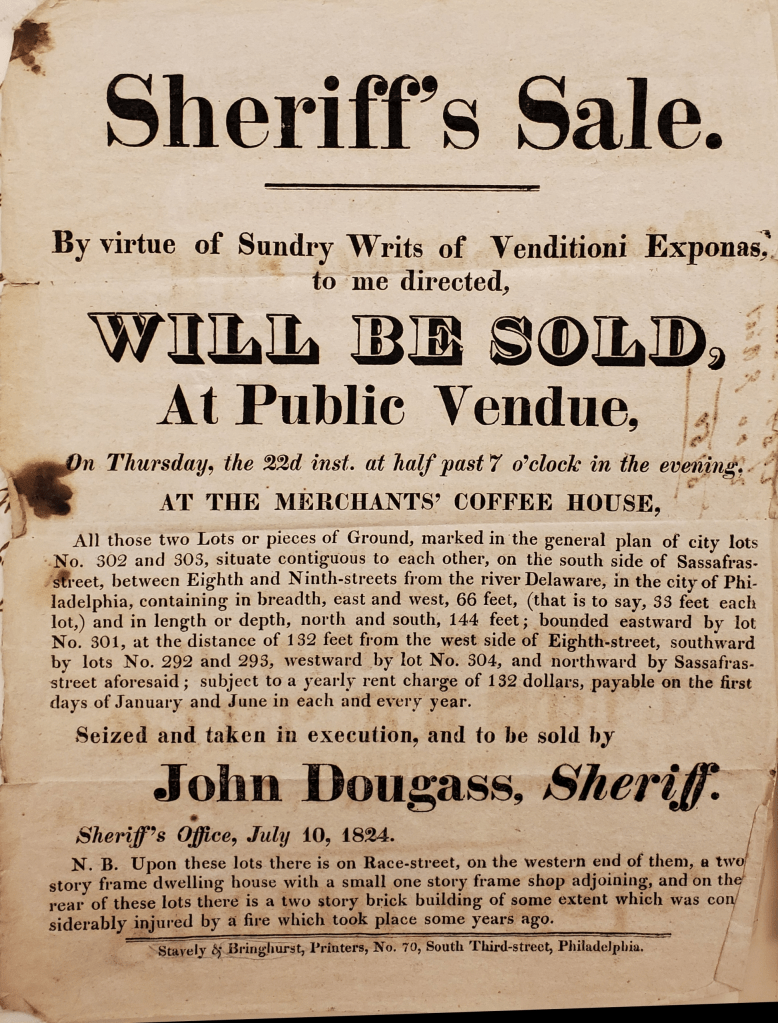

And yet, Douglass never attained the distinction of becoming Philadelphia’s mayor. But he served as an alderman until Dec. 15, 1823—having remained in the office for over 20 years. That year, Governor Heister appointed him as high sheriff of the city and county of Philadelphia. The later years of John Douglass’s life will be explored in further additions to this article.

PART III — THE FINAL DECADES

Family developments — and tragedies

While John Douglass was embroiled in the machinations of Philadelphia politics, significant family events were taking place. His eldest son, the cabinet maker John Jr., married Hannah Miller, a young woman from Lancaster County, in April 1800. A number of children were born to them—among the children were Elizabeth Crispin Douglass in February 1803, Joseph M. in 1807, and George H. soon afterwards.

Several of John Douglass’s sons—Joseph, Isaac, Neals, and Jacob—went to sea. Their adventures must have caused great trepidation for the Douglass family. One son was captured and imprisoned by the piratical monarchy of Tripoli, two others were captured by the British, and the fourth was lost forever in unclear circumstances.

The first to ship out might have been Isaac, who signed onto the ship Calliope bound for Batavia, Java. Isaac gave his age as 18, but more likely, he was 16 at the time. He was described as 5 feet, 7 inches tall, with a light complexion. That voyage, halfway around the world, probably took close to a year.

While Isaac was at sea. his older brother Joseph joined the U.S. Navy frigate Philadelphia as head sailmaker. He sailed in 1803 to serve in the war against the Tripoli pirates who had been attacking U.S. shipping in the Mediterranean. On Oct. 31, 1803, after futilely chasing an enemy corsair, the Philadelphia was wrecked on a rocky shoal and later captured. Joseph was taken prisoner with the other officers and crew members, and confined in the castle of the Bashar of Tripoli. They were only freed with the signing of the peace treaty on June 3, 1805. Back in Philadelphia, Joseph began a career as a sailmaker.

In the meantime, in November 1805, Isaac was listed in the crew of the ship Liberty, under Samuel Singleton, master. They were bound for “one or more ports of Europe.” Once again, Isaac gave his age as 18 (probably accurately this time). As it turned out, they sailed to Lisbon, and from there (on April 29), to St. Petersburg, Russia, and arrived back in Philadelphia on Sept. 10, 1806.

A few months earlier, on May 23, 1806, Neals Douglass, 21, had applied for his Seaman’s Protection Certificate. Neals went before a city alderman, accompanied by his older brother Abraham, to obtain the papers. Neals was described in the document as being five feet, six 1/2 inches tall, with a fair complexion, sandy hair, with a large red mark on his left cheek. At the time, Neals was living on South Street.

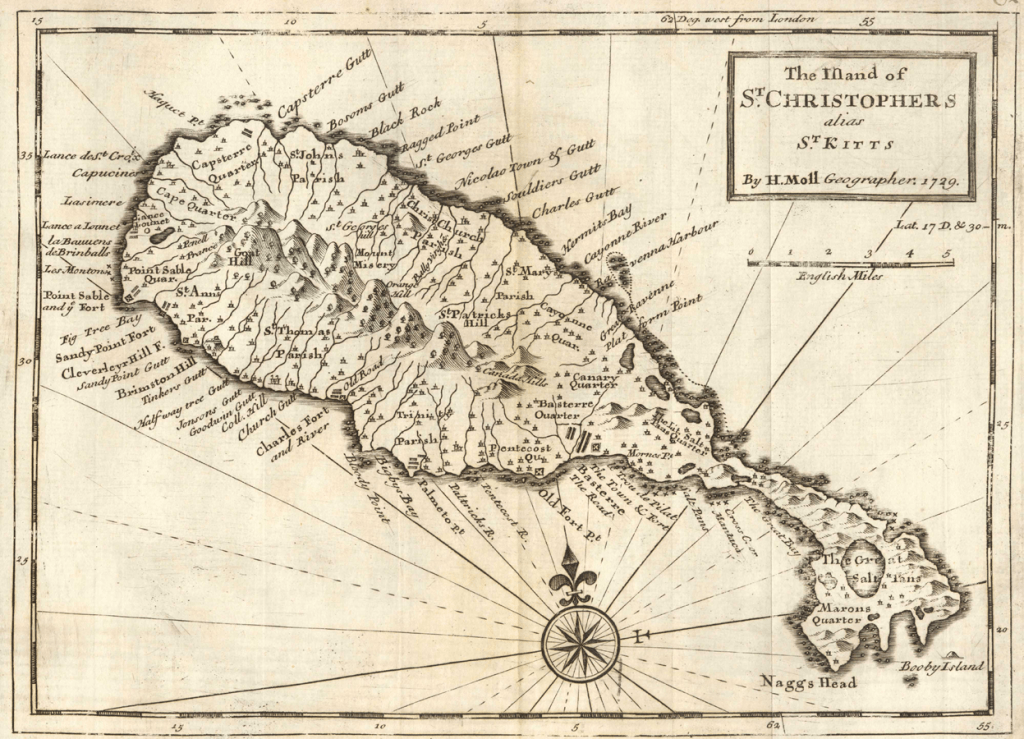

It appears that Neals signed onto the brig Mildred in November 1806, bound for La Guira, Mexico, under Capt. William Spence. The Mildred was a new vessel, 75 feet long on deck, and built in Kentucky. The brig encountered a storm in the Atlantic and lost her mainmast, but that was soon repaired. Some weeks later, the Mildred was detained in the Caribbean by the British frigate Ethalian, and suspected of concealing gunpowder in barrels of flour. The brig was sent into St. Kitts for trial (The United States Gazette, Feb. 18, 1807), while the supercargo, P.M. Connor, remained in Antigua to face the charges.

On Feb. 18, just as the news of the capture was hitting the Philadelphia newspapers, the Mildred and her cargo were released, after the claimants had paid all costs. But she was rapidly detained again “on suspicion of having a Spanish permit.” Finally, after being held for over two months, and with all costs, damages, and expenses having been paid, the brig and her crew were allowed to sail for La Guira. The Mildred left La Guira around the 1st of May, was briefly captured again by a British brig, and arrived back in Philadelphia on June 11 with a cargo of coffee, cocoa, indigo, hides, and cows’ horns. Finally, the brig Mildred herself was put up for sale.

On July 29, the brig Mildred, under new owners but again commanded by Capt. Spence, was cleared to sail to the River Platt (Argentina). But it appears that Neals Douglass stayed behind. A month later, on Aug. 29, John Douglass, as an alderman, wrote a note stating that his son Neals had appeared before him in person and had testified that Capt. Spence had taken his Seaman’s Protection document with him to sea on the Mildred. Douglass asked the captain to return the paper to the customhouse when he returned to Philadelphia.

Finally, their slightly younger brother, Jacob, at age 18, sailed on the ship Maysville, under master Philip Ryan, to St. Kitts. He left port on Sept. 5, 1806, and arrived at the island a few weeks before his brother Neals was held there on the brig Mildred.

In the summer of 1807, Jacob signed onto the Young Elias, a “fast sailing Philadelphia-built ship,”commanded by Capt. Dandelot. The departure was delayed for weeks, but finally on Oct. 24, the ship was cleared to sail to Bordeaux, France. Once having entered European waters, the ship was waylaid by the 36-gun British frigate Emerald and charged with having visited the French port of Rochelle, after the British had warned her not to enter. Paulson’s American Daily Advertiser (Feb. 5, 1808) reported that “after landing her passengers on the Isle of Rhea,” the Young Elias “was detained and ordered for England.” After trial in Plymouth, the cargo was restored, but the British captors appealed, and it is not clear whether the Young Elias ever returned to Philadelphia.