By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

A lot of the talk in Philadelphia in the spring of 1788 concerned the Grand Federal Procession, which was planned for the July 4 holiday. The event’s creators envisioned the event as a way to boost support for the proposed U.S. Constitution by linking it with the annual celebration of the Declaration of Independence. Similar activities were being organized in other cities, but the procession in Philadelphia was designed as the national centerpiece.

The Grand Procession was meant to demonstrate the political unity of people of different social classes in the years immediately following the American Revolution—at least among the urban population. Small tradesmen and artisans played a prominent role in the event. Within a short amount of time, however, that unity would fracture as social classes began to solidify and disparities in wealth increased.

The primary organizers of the event were men who would become associated with the emerging Federalist Party, the grouping that was most closely associated with the top financial and merchant interests of the North. Stark divisions between the Federalists and Jefferson’s Democratic Republican Party would develop several years later. In fact, the populist-minded slaveholders and anti-Federalists Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were among the leading initiators and authors of the Constitution.

As it happened, many of the men who had signed and formulated the Constitution, while they spoke of democracy, favored a centralized federal government that would serve to dampen the active participation and power of the common people. Most of the Constitution’s vaunted “checks and balances” were checks against popular democracy, thanks to features such as a Senate that was unelected, a lifetime-sitting Supreme Court that was also unelected, an executive branch with veto powers that was not directly elected, and a House that was elected only by highly restricted suffrage rights.

These items were especially intended to facilitate the interests of two major social classes—the wealthy merchants and financiers of the urban North and the slave-holding planters of the South. Both of these classes contained among their number many speculators in land and Continental debt certificates; the provisions of the Constitution would smooth their way toward getting full returns on these investments.

Most glaringly, the Constitution enabled the perpetuation of slavery, and even outlined the legal means by which escaped slaves could be recaptured and returned to their “owners.” This was an uncompromising demand of the Southern planters; slaves were a major portion of their wealth. Since enslaved Blacks could be bought and sold, could be transported at will from one plantation to another, and could procreate and produce more slaves—and since the cost of their upkeep was minimal—they often had more value than the land itself.

In general, the small artisans and tradesmen of Philadelphia and other cities also tended to support the Constitution. They believed, for example, that the new government’s powers to make treaties and to enact taxes would stimulate the export trade, promote domestic manufacturing, and penalize competitive foreign goods with duties and excises.

Opposition to the Constitution was mainly expressed in Pennsylvania by legislators from rural districts, whose small- farmer constituents saw that it would abrogate measures that had been passed or contemplated by the revolutionary state government such as paper money, low-cost credit, debt relief, and land banks. In fact, most districts west of the Susquehanna, and a good section of the state’s mid-section, were against the federal Constitution.

A small number of Philadelphia leaders—notably, Pennsylvania Supreme Court Judge George Bryan and his son Samuel—also maintained staunch opposition to the document. The Bryans and their co-thinkers believed that it negated many of the democratic principles espoused by radicals during the American Revolution. They stood against such features as a bicameral legislature—labeling the U.S. Senate “aristocratic”— lack of prohibition of a standing army, lack of a Bill of Rights, and infringement of the rights of individual states and districts.

Samuel Bryan, writing under the pseudonym of “Centinel,” and fellow “Anti-Federalists” found a forum for their views in the Independent Gazeteer. The newspaper was published by Eleazer Oswald, who also ran the London Coffee House on Market Street—formerly operated by another radical printer, William Bradford. Bitter polemics between Anti-Federalists and proponents of the Constitution were slung back and forth in his paper and others, and the Anti-Federalists even became victims of physical attacks. After several rural legislators had walked out of the state Constitutional Convention in protest against the proposal for elections to take place merely ten days after the first public reading, a posse was sent to break down the door of their boarding house, and forcibly carry them back to their seats.

The opponents of the Constitution lacked the means and organization to effectively counter the onslaught by the Federalists. The Constitution was approved in Pennsylvania by only 6800 votes, but about 82 percent of the electorate failed to vote at all. Later, against strong opposition, the Bill of Rights was added to the body of the Constitution in order to convince several other states to ratify the document. By the following July 4, tensions had eased greatly, at least in the city, and the Grand Federal Procession had tremendous support.

Trumpeting the cause of the “common man”

The key organizer of Philadelphia’s festival was Francis Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration and a Federalist supporter of the Constitution. Hopkinson was a diminutive man, with a pixie-like countenance and a head that John Adams described as “not bigger than a good-sized apple.” But despite its size, Hopkinson’s head was bursting with ideas gained from his many intellectual and artistic pursuits. His plan for the Grand Federal Procession was no doubt inspired by the masques and processions of Old World nobility. And he probably found an additional model in the craft processions that were common in towns of Britain, as well as in the Masonic processions of Philadelphia.

Despite its historical antecedents, however, the content of this festival was new, even revolutionary—trumpeting the cause of the common man. And while detractors of the Constitution described it as an “aristocratic” device, the main organizers of the procession attempted to demonstrate that artisans and small tradesmen were integral to the construction of the federal republic, and therefore gave them a central role in enacting the spectacle.

At daybreak, a salute rang out from the bells of Christ Church steeple. Almost immediately, the ship Rising Sun, anchored off Market Street, discharged its cannon. The vessel was decorated with flags of nations in alliance with the United States. Activities on the river played a major role in the event, befitting Philadelphia’s role as the major port of the new nation. Hopkinson noted in his account of the festivities that “ten vessels, in honour of the ten states of the present union, were dressed and arranged the whole length of the harbour; each bearing a broad white flag at the mast-head, inscribed with the names of the states respectively in broad gold letters.”

The ships were arranged like a map of the states from south to north. Residents of the district of Southwark could easily spot the ship Georgia lying off Cedar (South) Street. Two streets to the north, at the foot of Society Hill near Pine Street, was the ship South Carolina, and the Virginia lay off Spruce Street. Maryland was at Walnut Street, Delaware at Chestnut, and Pennsylvania at the “keystone” position of Market Street, near the Rising Sun. Likewise, the ships named for New Jersey, New York, and the New England states were anchored opposite the streets of the northern portion of the city.

“The ships along the wharfs were also dressed on the occasion;” Hopkinson wrote, “and as a brisk south wind prevailed through the whole day, the flags and pennants were kept in full display; and exhibited a most pleasing and animating prospect.”

Thousands took part in the parade

The pageant assembled around eight in the morning at Third and South Streets. It was a neighborhood predominantly made up of people from the working classes, though the large townhouses of wealthy merchants like William Bingham and Thomas Willing were merely several streets away. “Nine gentlemen,” wrote Hopkinson, “distinguished by white plumes in their hats, and furnished with speaking trumpets,” had been placed in charge of organizing the procession. It was probably useful for the purposes of keeping order that eight of the nine were high military officers.

At half past nine in the morning, the parade stepped off, winding its way three miles through Philadelphia and into the countryside. The procession was more than a mile and a half long and comprised over 5000 marchers, while thousands of others stood by the side to cheer them on. Many of the bystanders had participated in preparations for the event, sewing banners and helping the carpenters to build the floats. All the streets along the route had been well swept, probably by impressed prisoners from Walnut Street Prison. The trees had been trimmed, and the beggars told to move on.

The weather was perfect for a parade. As the sun peaked intermittently through fast-moving clouds, the temperature remained mild. Leading the march was Colonel Philip Pancake, who later commanded a militia unit against the Western farmers in the Whiskey Rebellion.

The contingent of city officials was headed by the high sheriff and the coroner, both on horseback. They were followed by members of the Board of City Wardens, the city treasurer and secretary, and the clerks of the public markets (with their scales and measures in hand). Then came the chief constable, Alexander Carlisle, with his two assistants, each bearing their staves. A musical band came next, followed by twenty watch- men, in uniform and holding their lanterns and rattles. The watchmen called the hour as such: “Ten o’clock, and a glorious starlight morning!” in an allusion to the ten states that had so far adopted the Constitution. And twenty silent watchmen brought up the rear.

Eighteen-year-old Benjamin Franklin Bache, who had recently returned to Philadelphia from France and was working in his grandfather’s print shop, produced a pamphlet detailing the order of each contingent in the parade. Perhaps some of the lower-class onlookers in the vicinity of Third and South Streets remarked on the fact that the lead contingent of this celebration of popular democracy was occupied by wealthy merchants, bankers, clergymen, and other members of the “better” classes, along with major officeholders in the federal government. But there is no record of jeers being hurled at the marchers—only cheers. As mentioned above, stricter divisions along class and party lines would come about only in later years.

Shopkeepers and men and women engaged in the crafts were grouped in forty-four contingents according to their trade. The contingents were separated by cavalry and militia units, or by musical bands. Many of the marchers carried their tools with them or wore their leather aprons. Each grouping was demarcated by guild banners and colored flags embroidered with slogans—many speaking out strongly for republicanism and the cause of the common people. The bricklayers carried a banner stating, “Both buildings and rulers are the works of our hands.” The house, ship, and sign painters proclaimed, “Virtue alone is true nobility.”

Bakers handed out fresh bread, which they had baked in an oven on their float. Their banner proclaimed, “May the federal government revive our trade.” On the metal workers’ float, journeymen engaged themselves in constructing a howitzer, which was fired at the end of the procession. A master coach maker, together with a harness maker, a wheelwright, painter, and other craftsmen constructed an ornamented carriage. A saddler and his assistants completed a leather saddle during the march, while blacksmiths reworked some old swords into a set of plough-irons and a sickle. Boat builders assembled a skiff, cordwainers in white aprons cobbled shoes and boots, gunsmiths fabricated small arms, and sailmakers stitched their products on a stage “representing the inside view of a sail-loft.”

“Protect the manufacturers of America!”

Physician Benjamin Rush, in a letter written immediately after the event, commented on the significant presence of working people in the procession: “It was very remarkable, that every countenance wore an air of dignity as well as pleasure. Every tradesman’s boy in the procession seemed to consider himself as a principal in the business. Rank for a while forgot all its claims, and Agriculture, Commerce and Manufactures, together with the learned and mechanical professions, seemed to acknowledge, by their harmony and respect for each other, that they were all necessary to each other, and all useful in cultivated society.

“These circumstances distinguished this Procession from the processions in Europe, which are commonly instituted in honor of single persons. The military alone partake of the splendor of such exhibitions. Farmers and Tradesmen are either deemed unworthy of such connections, or are introduced like horses or buildings, only to add to the strength or length of the procession. Such is the difference between the effects of a republican and monarchial government upon the minds of men!”

As a demonstration of the possibilities afforded by developments in technology, a carriage pulled by ten bay horses contained a cotton-carding machine worked by two persons, who maintained the level of production that it had formerly been necessary to employ fifty people to carry out. A large spinning machine drew cotton fiber for “fine jeans or federal rib.”

Benjamin Rush, obviously inspired by the float, observed, “Cotton may be cultivated in the southern, and manufactured in the eastern and middle states, in such quantities, in a few years, as to clothe every citizen of the United States. Hence will arise a bond of union to the states, more powerful than any article of the New Constitution.” The float was sponsored by the Society for the Promotion of Manufactures, and its banner declared, “May the union government protect the manufactures of America!”

A similar sentiment, which called on consumers to buy American-made products, was expressed by the slogan that the brewer Luke Morris carried on his standard: “Home Brew is Best.” Reuben Haines led the brewers’ contingent. Barley stalks sprouted from the men’s hats, and they each held poles with banners depicting hops, malt shovels, and mashing oars.

The float of the printers carried dancer and puppeteer John Durang, who portrayed Mercury, the winged messenger of the gods. Benjamin Franklin’s daughter, Sarah (“Sally”), made his costume. Durang later recollected, “Dr. Franklin was in the room at the time she fit the cap on my head. The dress was flesh couler, the cap and sash blue, the wings of feathers.” The printers used a press on their float to stamp out copies of a song, supposedly composed by Benjamin Franklin, which was distributed to onlookers. Durang tied the song sheets to the legs of doves, which he then released to the skies:

Ye merry Mechanics, come join in my song,

And let the brisk chorus go bounding along;

Though some may be poor, and rich there may be,

Yet all are contented, and happy, and free.

Ye Tailors! Of ancient and noble renown,

Who clothe all the people in country or town,

Remember that Adam, your father and head,

The lord of the world, was a tailor by trade …

And Carders, and Spinners, and Weavers attend,

And take the advice of Poor Richard, your friend;

Stick close to your looms, your wheels, and your card,

And you never need fear of the times being hard …

Ye Shipbuilders! Riggers! And Makers of Sails!

Already the new constitution prevails!

And soon you shall see o’er the proud swelling tide,

The Ships of Columbia triumphantly ride.

At least seventy tobacco merchants participated in the parade; each of them wore a green apron, with different kinds of tobacco leaves protruding from his hat. This contingent illustrated the uneven and discriminatory nature of the support for the U.S. Constitution since its industry was based on a product that was grown by slave labor in the South. The noted merchant and industrial innovator Thomas Leiper, who had a leading position in the parade, personalized these contradictions. Although he was a strong Jeffersonian and anti-Federalist, Leiper served as a leading officer in Philadelphia’s light-horse militia, which acted to help quell several anti-government uprisings, including the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 and the Fries Rebellion of 1798.

Leiper held the white silken banner of their contingent, which bore the motto, “Success to the Tobacco Plant.” A painting on the banner depicted the plant as a metaphor for the Federal Union; it was shown with thirteen leaves—ten in perfection and three still not matured. On one side of the plant was a hogshead of tobacco, a roll of plug tobacco, and a bottle and bladder of snuff. On the other side were shown thirteen stars—ten silvered and shining bright, and three left unfinished.

The Grand Federal Edifice

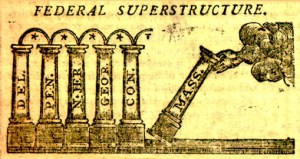

The justices of the Supreme Court rode on a float shaped like a giant eagle. Other floats represented the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the new U.S. Constitution. One float, drawn by ten white horses, contained the Grand Federal Edifice, a Roman-style circular pavilion, thirty-six feet high. This was the main emblem of the event. It had been designed by artist Charles Willson Peale and constructed by members of the Carpenters’ Company. The thirteen Corinthian columns that supported the dome symbolized the original states of the Union; the conception put forward by Peale and Hopkinson was that without the dome to unify them, the thirteen individual columns would topple. Three of the columns were incomplete, signifying the states (New York, Rhode Island, and North Carolina) that had not yet ratified the Constitution. A cupola representing the new federal government surmounted the dome, with the figure of Plenty, cradling her cornucopia, at the crown. At the base of the Edifice, the motto “In Union the Fabric Stands Firm” had been inscribed.

The other major float in the parade was the Federal Ship Union. The vessel was actually seaworthy and constructed out of the barge that had once belonged to the British frigate Serapis, captured by John Paul Jones at the battle of Flamborough Head. For years after its use in the procession, the vessel lay at anchor in the Schuylkill River, where it was illuminated at night as a tourist attraction attached to the pleasure grounds at Gray’s Ferry. Eventually, the Federal Ship Union was sunk in deeper water nearby.

The parade lasted for over three hours, as participants marched in a zigzag pattern to Callowhill Street (in the northern suburbs), west to Fourth, retracing the route south to Market, west to Broad, and finally north again to the slopes of Bush Hill (near present-day Sixteenth and Callowhill Streets). A century earlier, the land had been part of William Penn’s Springettsbury Manor, which the Penn family later subdivided into estates—the largest being granted to attorney Andrew Hamilton.

At the crest of the knoll stood Bush Hill mansion, now owned by William Hamilton, Andrew’s grandson, whose main residence was the fashionably remodeled Woodlands mansion on the west bank of the Schuylkill. Hamilton had been a collaborator with the British during the early years of the Revolution, but had since reconciled himself to the new government and accepted the use of Bush Hill’s lawns for the celebration of the national Constitution. The site for a while became known as Union Green, and John Adams occupied the mansion in 1790-91, when he served as vice president.

James Wilson on representative “democracy”

A lunch was served to the thousands of marchers assembled on the green. According to Tench Coxe of the government accounting office, the assembly consumed 4000 pounds of beef, 2600 pounds of gammon (smoked ham), thirty barrels of our, 500 pounds of cheese, thirteen hogsheads of cider, and 100 barrels of strong beer.

The luncheon tables were set in a large circle, at the center of which was placed the Grand Federal Edifice, with the Federal Ship Union to one side. Onlookers might have recognized the large frame of James Wilson, who rose from his table within the Edifice, balanced his spectacles on his nose, and proceeded to give the main discourse on the event.

In his lengthy and animated speech, Wilson contrasted the new federal Constitution, and the republican government that it established, with ancient examples of democracy that were, in reality, unable to reflect the will of the people: “You have heard of Sparta, of Athens and of Rome. You have heard of their admired constitutions, and of their high prized freedom. In fancied right of these, they conceived themselves to be elevated above the rest of the human race, whom they marked with the degrading title of Barbarians. But did they, in all their pomp and pride of liberty, ever furnish to the astonished world an exhibition similar to that which we now contemplate?

“Were their constitutions framed by those, who were appointed, for that purpose, by the people? After they were framed, were they submitted to the consideration of the people? Had the people an opportunity of expressing their sentiments concerning them? Were they to stand or fall by the people’s approving or rejecting vote? …”

But after the Constitution had been ratified, what then? Would the people still govern? Wilson declined to address the possibility of direct popular assemblies, let alone protests in the street, as had taken place during the recent revolutionary years. Now, democracy was to be relegated to a regular procedure in which the electorate (at that time limited to white propertied men) would vote for an erudite and presumably “wise and good” grouping to represent them in the halls of government:

“Allow me to direct your attention,” he enjoined his listeners, “in a very particular manner, to a momentous part, which, by this Constitution, every citizen will frequently be called to act. All those in places of power and trust will be elected either immediately by the people; or in such a manner that their appointment will depend ultimately on such immediate election. All the derivative movements of government must spring from the original movement of the people at large. If, to this they give a sufficient force and a just direction, all the others will be governed by its controlling power.

“To speak without a metaphor; if the people, at their elections, take care to choose none but representatives that are wise and good; their representatives will take care, in their turn, to choose or appoint none but such as are wise and good also.” Wilson’s address received an ovation, after which the distinguished men at Wilson’s table drank ten toasts in honor of the then ten confederated states. Each toast was followed by cannon fire, to which the ship Rising Sun, lying in the Delaware, responded with its own volley.

However, it might have occurred to people from the middling classes who were able to hear Wilson’s words from the edge of the crowd, or who read it several days later when it was reprinted in newspapers, that Wilson was a peculiar candidate to be lecturing them about democracy since he had often expressed himself as an ardent opponent of Pennsylvania’s democratic 1776 constitution. Many probably remembered that seven months earlier, during a Federalist celebration in Carlisle, an angry group of protesters had attacked Wilson with barrel staves and clubs. The following day, Carlisle’s anti-Federalists pitched an effigy of Wilson into a bonfire, along with that of state Supreme Court Justice Thomas McKean.

And the Carlisle incidents certainly brought memories to the fore of the armed attack on Wilson’s house at Third and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia in 1779. The “Battle of Fort Wilson” had been initiated by disgruntled Pennsylvania militiamen who were demanding payment of their wages. Only the timely intervention of Timothy Matlack, who had brought along a mounted guard, convinced the rioters to back away from their confrontation with Wilson and other political leaders sheltering inside the house. Yet Wilson certainly had support in some quarters, and the Federalists had become by far the predominant organized party in Pennsylvania.

The following January saw the first election for president of the United States, with George Washington as the candidate. In Philadelphia the Federal ticket for electors, headed by James Wilson, was successful, as was the case throughout the state. But political tensions began to seethe between the Federalists and oppositional forces that later coalesced into the Jeffersonian Democratic Republican party. The conflict burst to the surface a decade later, influenced in part by the egalitarian spirit of the French Revolution and moves by the John Adams administration toward a war with France. The apparent unity symbolized by the Grand Federal Procession quickly flew apart.