By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

John Henry Nezmos (also spelled Nesmoz, Nesmos, etc.) led a short but adventurous life as a mariner. He was born about 1787 as the son of Benedict Nezmos—an immigrant from Lyon, France, who worked as a Philadelphia chocolate maker*—and Rebecca Wood. Rebecca was the daughter of William and Margaret (Boyce) Wood, who owned farmland next to Cobb’s Creek in the southwest portion of Philadelphia County.

John Henry was baptized at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in July 1792 (the church records state that he was nine years old, but more likely, he was about five). Tragically, his father, Benedict, died in November 1793. His death came at the tail end of Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of that year; he appears in the list of victims compiled by Mathew Carey in the 4th edition of his published chronicle of 1793, “A Short Account of the Malignant Fever.” One of Benedict’s sons and a daughter also died that year. At the time, the family was residing at 345 S. Second St., at the corner of Catharine St. in the district of Southwark.

In June 1795, Rebecca Nezmos, Benedict’s widow and the executrix of his will, petitioned the County Orphan’s Court to approve William Robinson Sr. as the legal guardian of her two children, John Henry and his sister Deborah. The reference might have been to the William Robinson who was a justice of the peace, living at 330 S. Front Street, at the corner of Meade Alley (later Fitzwater Street) in Southwark. A couple of years later, Rebecca married a schoolteacher, Andrew Suplee. After the death of her second husband, in about the year 1800, Rebecca, still living in the house on Second St., earned money as a seamstress.

On Nov. 5, 1805, at 18, John H. Nezmos shipped out on the brig Susannah (Capt. Thomas Morgan) from Philadelphia to Barbados. Nezmos was described in the register of the Philadelphia Custom House as being almost 5’ 5” in height, with light brown hair and dark grey eyes. The paper states that he was born in New York, but that is uncertain.

On Dec. 13, 1810, Nezmos, then 23, married Rebecca Middleton at the Fifth Baptist Church. She was the daughter of George and Mary (Workman) Middleton. (Mary Wood, the sister of Nezmos’ mother, had married William Middleton; Rebecca’s family might have been related to them.) Records of the First Presbyterian Church state that Rebecca was born on March 7, 1791, and baptized in 1793.

Just days after his marriage, John H. Nezmos sailed to Newry, Ireland, on the ship Maysville under Capt. Jacob Baush. Nezmos appears to have served as first mate on the voyage—a significant step upward in rank and pay.

Less than a year later, in 1811, Nezmos wrote a will—perhaps sensing the dangers that presented themselves at sea. In the document, he mentioned his wife Rebecca and his infant son, Benedict. Also mentioned were his mother, Rebecca Suplee, and his uncle William Middleton.

During the next couple of years, which include the outbreak of the War of 1812, Nezmos’ activities are uncertain. Evidence suggests that he might have volunteered at one point as a private in Capt. Coryell’s company of the Pennsylvania militia. On Sept. 11, 1814, he is recorded as applying to serve as a lieutenant in the company. He wrote a letter from Kennett Square, Pa., two days later complaining to his superiors that the company’s rifles were unfit for service (the letter is now displayed in the Pennsylvania Archives). A little more than a week after that, on Sept. 22, his three-year-old son, Benedict, died and was buried in the graveyard of the Third Baptist Church. At the time, the Nezmos family lived at 28 Argyle Street (later Almond St. and then Kenilworth St.). This was a small alley that ran from the Delaware River wharves up the hill to 337 S. Front Street, in the district of Southwark.

Nezmos was released from the militia on Jan. 3, 1815. Three months later, he received his first post as a sea captain, commanding the sloop Susanna with a crew of six to Santo Domingo. In December 1816, he was put in charge of the brig Joseph S. Lewis, which he took first to Cape Henry, Haiti, and later to Hamburg, Germany. At this time, the family was living on the corner of Front and Queen Streets in Southwark, a few blocks south of their previous residence. The Nezmos’ daughter Mary was born at this house in 1817.

On Oct. 13, 1817, the Joseph S. Lewis, under Capt. Nezmos, sailed from Philadelphia for Genoa, Italy. Apparently, the alarming rumor got back to Philadelphia that the Lewis had been captured in the Mediterranean by a Spanish warship. Spain was then fighting wars on two fronts — against other powers in Europe as well as against rebels in South America seeking independence from Spanish colonial rule. Although the rumor of capture proved to be untrue, the story of the Lewis demonstrates some of the perils of sea voyages during that era.

On March 9, 1818, Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser and other newspapers carried the following dispatch: “The reported capture of the brig Joseph S. Lewis, Capt. Nezmos, by the Spaniards, is erroneous, as will appear from the following extract of a letter from a gentleman in Gibraltar to the owners of the brig …

“GIBRALTAR, January 6, 1818 — We regret to inform you of the disaster which has befallen your vessel (the J.S. Lewis). After a long passage, she was driven through the Straits [of Gibraltar] on the 1st December in a heavy gale, and when lying to behind the Rock, was run down by a Spanish brig of war, had her bows broken in, and was forced to go into Carthagena, where she arrived on the 19th ult. A passenger from her has arrived in the Bay, and affords this information. We expect her every day.”

Indeed, within a few weeks, Capt. Nezmos and the Lewis entered port at Gibraltar (according to the American vice consul stationed there), and then sailed for Genoa. By May 26, 1817, they had reached Gibraltar again on the homeward voyage. After a brief visit with his family in Philadelphia, Nezmos was ready to command the schooner Emily on a short voyage to Cuba; they left port on Aug. 18, 1818.

Four months later, on a cold New Year’s Eve, Dec. 31, 1818, Nezmos took the brigantine Trident to Bermuda. The Trident was a new vessel, built that same year in order to supply regular packet service between Bermuda and Philadelphia. She was advertised as “a fast sailer” that “will constantly have a Delaware [River] pilot on board, carries about 900 Barrels” and that supplies “comfortable accommodations” for passengers (The Royal Gazette, Hamilton, Bermuda, March 27, 1819).

Although the Trident was built for speed, the return voyage turned out to be exceedingly slow due to heavy gales in the Atlantic. In fact, for two weeks they had to lie stationary, without sails, because of the winds. After 23 days at sea, on March 10, the Trident made port at Norfolk, Va., with a cargo of rum. They did not arrive back in Philadelphia until the end of March, and within days, they were ready for another run to Bermuda.

After five voyages to Bermuda on the Trident, hauling rum, molasses, and coffee, Nezmos was put in charge of the brig James Lawrence in early 1820. This would be the final vessel that he would command. The first voyage on the James Lawrence was chartered by the Philadelphia merchant Henry Pratt and was a long one; they left Philadelphia on March 27, 1820, bound for South America. In Rio de Janeiro, for a reason that is unclear, Capt. Nezmos was temporarily discharged from his post along with a boy serving on the vessel, Washington Osburn. A notation in the Philadelphia Custom House records states, “all the rest [of the crew] agreeable to rule,” so Nezmos and young Osburn seem to have resisted some sort of regulation. The James Lawrence then set off for Gibraltar on Aug. 29, and two weeks later made sail for Philadelphia, where they arrived after a 38-day voyage on Oct. 23.

After the brig had returned home, Pratt advertised the cargo as including over 100 casks of dry Malaga and other wines, well over 1000 boxes of Muscatel and Bloom raisins, and a box of Leghorn hats. Nezmos himself invested in five boxes of raisins, which he put up for sale. In this period, the Nezmos family was living at 82 Christian Street in Southwark.

In early 1821, the James Lawrence, again under the charter of Henry Pratt, voyaged to Aux Cayes, on the southern coast of Haiti. She returned to Philadelphia around Feb. 17 with a cargo mainly of coffee, plus some turtle shell, French peas, and oranges.

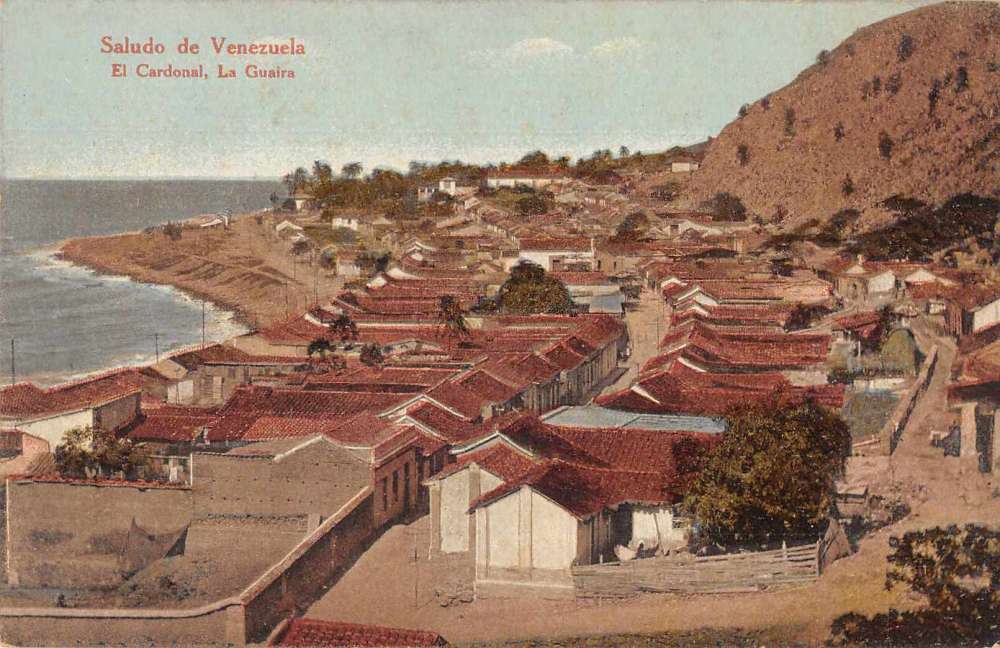

In the spring, the James Lawrence sailed to the Caribbean, and toward the end of April entered the harbor at La Guaira, the main port of Caracas, Venezuela. Unfortunately, the vessel had arrived in the midst of a civil war. After three years of conflict, Spanish royalist forces had attempted a new offensive to overthrow the rebels led by Simon Bolívar, who now controlled most of the area now comprising Venezuela and Colombia. After their defeat in Caracas, the royalists retreated from the city and retired to La Guaira. When their position there also proved indefensible, they decided to flee even farther, while spiking their guns and throwing the remaining ammunition into the sea. On the morning of May 15, 1820, sympathizers of the Spanish monarchy hastened to the docks at La Guaira, where they boarded a fleet of vessels under convoy of the Spanish frigate Ligera and escaped to Puerto Cabello—about 75 miles up the coast.

The James Lawrence and other U.S. vessels were able to escape to Puerto Cabello along with the fleet. Before the evacuation, the schooner Three Daughters of Baltimore, had her sails shredded by a number of shots, while seven cannonballs that struck her spars fell on the deck. Two weeks later, the schooner St. Helena was boarded by a party of patriot soldiers and detained 24 hours. However, the James Lawrence remained untouched, although Nezmos had to leave the supercargo (a man named Eckart) behind in Caracas when she sailed (Aurora General Advertiser, Philadelphia, June 26, 1821).

The James Lawrence arrived in Curaçao, an island off the Venezuela coast that was ruled by the Netherlands, about June 29. Two days later, John Henry Nezmos was dead. According to a short notice of his passing in Paulson’s Daily Advertiser (July 28, 1821), Nezmos died of yellow fever—the same disease that had taken his father and siblings. It is unlikely that he contracted the fever in Curaçao, since after a victim is bitten by a mosquito, the disease usually requires a longer amount of time than two days to become fatal. He was probably infected while in harbor in Venezuela; yellow fever was common along the coast of the country. Also, an epidemic had recently overwhelmed Havana, Cuba, and was hitting Barcelona and other Mediterranean ports in Spain, so a traveler might have brought the disease from one of those places.

The James Lawrence returned to Philadelphia on Sept. 21, 1821, but without the body of its captain. Rebecca, still living in the house on Christian Street, was brought the news that she was now a widow. Many years later, while applying for a government pension, Rebecca recalled that the first mate had told her that they buried Capt. Nezmos in La Guaira. Because of the fighting in La Guaira, however, it would have made little sense for the crew of the James Lawrence to return to that port to bury him. It is more likely that he was buried where he died—on the island of Curaçao.

The pension that Rebecca Nezmos sought cited her husband’s military service during the War of 1812. Rebecca first applied for it in 1855 and again in April 1866, when she appeared before federal officials in person; but she was refused. In these years, she was living at 35th and Market Streets with the family of her daughter, Mary England. Finally, on Feb. 14, 1871, she was granted payments of $8 a month. Unfortunately, she died just a year later and was buried on April 5, 1872, in the ground of Ebenezer Baptist Church, at Third and Christian Streets, just steps from the old home that she and her husband had shared.

- Ca. 1785 – 1794, John Henry’s grandfather, Jean-Baptiste Nezmos, partnered with James Valliant as owners of a grocery shop at 109 N. Second Street. Jean-Baptiste died in 1794, a year after his son Benedict.

Top drawing: From Thomas Rowlandson, 1815: “The English Dance of Death.”